Summary

Ned Block and others have argued for the hypothesis that phenomenal consciousness—what it's like to experience things—can be richer than what we can report or hold in working memory. Critics insist that the rich informational data in our brains is part of unconsciousness. I argue that because phenomenal consciousness is not a definite "real thing", this debate is merely about which definition of consciousness to use. While discussion of this topic illuminates important psychological discoveries, we may as well jettison the concept of "consciousness" from these discussions and replace it with more precise terminology.

Contents

Epigraph

I have watched more than one conversation—even conversations supposedly about cognitive science—go the route of disputing over definitions. [We can take] the classic example to be "If a tree falls in a forest, and no one hears it, does it make a sound?"

—Eliezer Yudkowsky, "Disputing Definitions"

A parable

A physics conference is being held next year, and 12 researchers are planning to submit papers. Those researchers have gathered raw data and synthesized it into more compact research findings. After the researchers write their draft papers, a freak accident causes their raw data to be lost, but it's ok because they've already developed higher-level summaries of their findings.

Due to time constraints, only 4 of the papers can be presented at the conference; the rest will go unheard, and the rejected researchers won't resubmit their current research elsewhere.

After the researchers finish their papers, they wait a bit for responses from the conference organizers. The conference organizers tell everyone that 12 papers have been submitted, without giving details about the contents of the submitted papers. The organizers then proceed to select 4 of the papers. Those papers are presented at the conference a few months later. The presented papers attract a lot of attention and spark further debate and inquiry. The 8 rejected papers don't have much impact because they weren't presented and were shelved.

Now we ask the question: Where did the actual research happen in this scenario? Was it at the stage when individual researchers were preparing their manuscripts? Was it only when the 4 accepted papers were presented? How can something be "actual research" if it isn't recorded in published conference proceedings for others to read?

These questions sound silly—as silly as debating whether "making a sound" really means (1) emitting acoustic vibrations or (2) the processing of such vibrations by someone's auditory cortex. Yet these definitional debates are common in the domain of consciousness, with one example being arguments over whether "Perceptual consciousness overflows cognitive access" (Block 2011), discussed below.

Sperling experiment

One of the cornerstones of Block's argument is Sperling's partial report procedure. I won't describe the details here, but they're well explained by Wikipedia or Block (2011). Block (2011) contends (p. 567): "According to the overflow argument, all or almost all of the 12 items are consciously represented, perhaps fragmentarily but well enough to distinguish among the 26 letters of the alphabet. However, only 3-4 of these items can be cognitively accessed, indicating a larger capacity in conscious phenomenology than in cognitive access." In other words, all 12 letters were phenomenally conscious, even though only 3 to 4 can be explicitly recalled. In the case of our parable from earlier, Block would presumably argue that the work of all 12 people who submitted papers to the conference counted as "actual research".

That said, Block would probably not go so far as to count raw data collection as "actual research". Block (2011) assumes that consciousness must be at higher neural levels than "the retina or early vision" (p. 567): "The neural locus of the high memory capacity demonstrated in the Sperling phenomenon is in brain areas that are candidates for the neural basis of conscious perception rather than in the retina or early vision [...], and so the Sperling phenomenon may reveal the capacity of conscious phenomenology." Pitts et al. (2014) concur: "no one has proposed retinal activity as a potential" neural correlate of consciousness.

Block (2011) describes a contrary interpretation of the Sperling results (p. 568):

The fact that subjects in such experiments often observe that ‘they saw more than they remembered’ [...] motivates the premise of the overflow argument that the information is conscious. However, many critics starting with Kouider and Dehaene have claimed that this information is not conscious until attended and accessed [...]. As Cohen and Dennett put it: ‘[p]articipants can identify cued items because their identities are stored unconsciously until the cue brings them to the focus of attention’ [...]. Advocates of this view do not regard subjects’ reports of a persisting conscious icon as wholly illusory; rather what some of them claim is that the conscious icon contains generic, non-specific, abstract or gist-like letter representation that are neutral between the shape of one letter and another [...].

In the case of our parable, these critics claim that "actual research" only includes the 4 research papers that were ultimately presented and had widespread impacts on subsequent discussion within the physics community. The perception of 12 research papers wasn't completely illusory, though, because the conference organizers did tell everyone that 12 papers had been prepared and submitted.

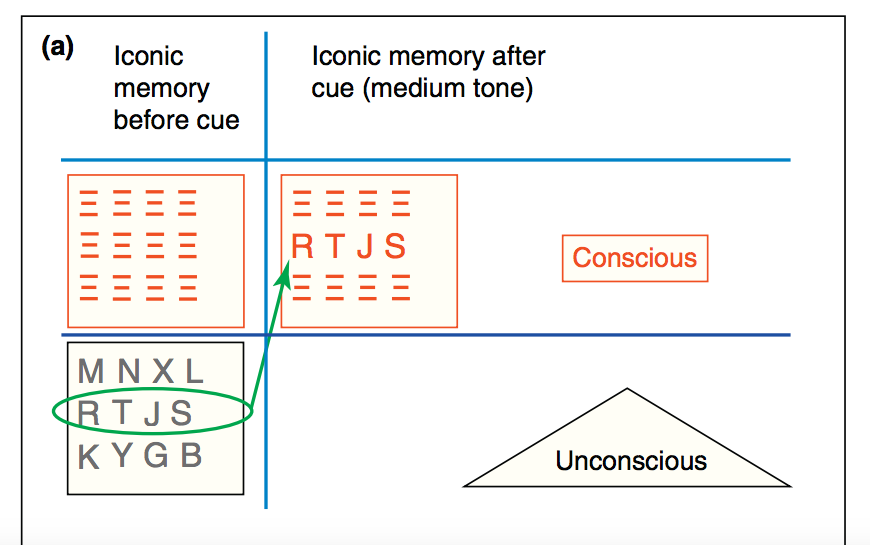

Block (2011) illustrates the view of his critics with the following diagram, which is Fig. 2(a) in his paper.

Block (2011)'s caption on this figure explains:

The upper left quadrant represents what is conscious in iconic memory prior to the cue – the ["three horizontal bars"] symbols are meant to indicate a phenomenal representation of a ‘gist-like’ or ‘generic letter’ that does not contain information sufficiently specific to decide among letters. The Sperling array is supposed to appear to the subject prior to the cue as an array of letters that don’t look like any specific letter. The lower left quadrant indicates that the specific information necessary to do the Sperling task is in an unconscious representation. The green ellipse represents attentional capture and amplification that is supposed to move the unconscious specific information necessary to do the task into consciousness. The upper right quadrant represents the contents of consciousness after the cue, in which the cued row is conscious. The upshot is that the information on the basis of which a subject does the Sperling task is in unconscious iconic memory with consciousness representing only a geometric array of generic gists plus fragmentary sparse features before the cue.

If you're interested in a further summary of this debate, see Box 5 of LeDoux and Brown (2017, SI).

Here's a hypothetical exchange to further explain my sense of the disagreement. I don't know if Block or his opponents would endorse these particular statements.

Overflow proponent: Subjects in the Sperling experiment say they can see all the letters. And the task itself shows that all the data are present in iconic and/or fragile visual short-term memory (Block 2011, p. 573), because any arbitrary row can be recalled. So if people say they see everything, and their brains really do store everything, why not accept that people really do consciously see everything?

Overflow opponent: People say they see everything because there's a generic representation of "12 letters there" that their brains generate. And the letter data are indeed present, but they're unconscious until specific letters are accessed by working memory.

Translating this dialogue into the language of our parable:

Overflow proponent: The conference committee says there are 12 actual research projects. And the selection process itself shows that all the research papers exist, because any arbitrary set of 4 papers can be selected. So if the committee says there are 12 research projects, and the 12 papers have all been drafted, why not accept that all 12 submissions are actual research?

Overflow opponent: When the conference committee says there are 12 actual research projects, they're issuing a general statement that "there are 12 submissions". And the paper drafts are indeed written, but they're not actual research until they're accepted and presented at the conference.

Global workspace

Block (2007) (p. 492) quotes Dehaene and Naccache (2001):

Some information encoded in the nervous system is permanently inaccessible (set I1). Other information is in contact with the workspace and could be consciously amplified if it was attended to (set I2). However, at any given time, only a subset of the latter is mobilized into the workspace (set I3). We wonder whether these distinctions may suffice to capture the intuitions behind Ned Block’s [...] definitions of phenomenal (P) and access (A) consciousness. What Block sees as a difference in essence could merely be a qualitative difference due to the discrepancy between the size of the potentially accessible information (I2) and the paucity of information that can actually be reported at any given time (I3). Think, for instance, of Sperling’s experiment in which a large visual array of letters seems to be fully visible, yet only a very small subset can be reported. The former may give rise to the intuition of a rich phenomenological world – Block’s P-consciousness – while the latter corresponds to what can be selected, amplified, and passed on to other processes (A-consciousness). Both, however, would be facets of the same underlying phenomenon.

In our parable analogy, I1 could be raw physics data that feeds into analysis but isn't directly published. I2 is the set of all papers that could potentially be published, but only papers in the set I3 are actually presented. Both the unpublished and published papers are "facets of the same underlying phenomenon."

Block (2007) replies (p. 492): "The distinction between I1, I2, and I3 is certainly useful, but its import depends on which of these categories is supposed to be phenomenal. One option is that representations in both categories I2 (potentially in the workspace) and I3 (in the workspace) are phenomenal. That is not what Dehaene and Naccache have in mind. Their view [...] is that only the representations in I3 are phenomenal." We might rewrite Block (2007)'s quote: "The distinction between raw data, drafting a paper, and presenting at a conference is certainly useful, but its import depends on which of these categories is supposed to be actual research. One option is that both drafting papers and presenting accepted papers are forms of actual research. That is not what Dehaene and Naccache have in mind. Their view [...] is that only conference presentations are actual research."

The core disagreement is not empirical

In an interview (Tippens 2015a), Block summaries the disagreement between him and his critics:

The key issue is: does the attentional bottleneck come between unconscious perception and conscious perception? That’s [one critic's] view. Or does the attentional bottleneck come after conscious perception, between conscious perception and cognition? That’s what I think. So I think that you consciously perceive many things and the bottleneck comes between conscious perception and cognition. You can only cognize a few of them. [My critic] thinks it’s unconscious perception that sees too many things. And you can only phenomenally appreciate a few. So those are the two views.

But these views—or at least the simplistic caricatures in Block's quote—only differ on the matter of where the boundary of a mysterious thing called phenomenal consciousness lies—or, less charitably, where the Cartesian theater begins. These (perhaps oversimplified) views don't differ on any functional details. For those like me who don't believe phenomenal consciousness is a privileged thing, the dispute is purely verbal.

Block claims that "There have been quite a few experiments lately that support my side of the disagreement" (Tippens 2015a). But as far as I can tell, all the evidence that Block or his critics can mount is equally consistent with any view of where phenomenal consciousness begins or ends. If one side says "process X is conscious", the other side can just say "no, process X is part of the unconscious; only process Y is conscious".

For example, Block cites as evidence for his view an experiment in which people's brains were measured during a task, and they weren't asked whether they were conscious of background objects, like a square, until afterward (Tippens 2015b). "what [the experimenter] found is that awareness of the square correlated with activity in the back of the head" (Tippens 2015b). But, says Block, reporting what you see tends to use the front of the head (Tippens 2015b). So people can be conscious of something without engaging the neural machinery of active report at the time. This is a reasonable view, but perhaps critics could allege that the information about the square was unconscious during the task, and it only became conscious afterward when attention was directed toward it by later reflection. (I'm just making up this particular criticism, but it seems like something someone might say.)

Imagine that you're colonizing a new planet, and country boundaries haven't yet been divided up. The artificial boundaries can be placed anywhere, without regard to the underlying terrain (although marking boundaries at, say, rivers or isthmuses may be more useful than marking boundaries in other places). Different parties could cite various geographical studies that support their preferred territorial boundaries. But ultimately, it's not an empirical question. There is just the territory, and it can be artificially partitioned any way you choose.

Overgaard and Grünbaum (2012) (p. 137) seem to agree with me that the debate between Block and his critics "is grounded in pre-empirical definitions, eventually deciding what may be used as a measure of conscious experience in experiments. [...] As neither position can be stated in an empirically falsifiable manner, the debate cannot itself be resolved by empirical data."

Blackmore (2016):a "Are there actual, but unobservable, facts about which processes, thoughts or actions were conscious at any time? I say no. The neural correlates of all these would in principle be observable but with no way of distinguishing between conscious and unconscious ones either by objective measures or in subjective experience. The distinction is meaningless because consciousness is an attribution we make, not a property of events, thoughts, brain processes or anything else."

"Presumably there is a fact of the matter"

Block (2007) grapples with the general question of "whether cognitively inaccessible and therefore unreportable representations inside [cognitive] modules are phenomenally conscious" (p. 481). "For example, one representation that vision scientists tend to agree is computed by our visual systems is one which reflects sharp changes in luminosity; another is a representation of surfaces (Nakayama et al. 1995). Are the unreportable representations inside these modules phenomenally conscious?" (p. 481)

Block (2007) suggests that one might try to solve the problem as follows:

Determine the natural kind (Putnam 1975; Quine 1969) that constitutes the neural basis of phenomenal consciousness in completely clear cases – cases in which subjects are completely confident about their phenomenally conscious states and there is no reason to doubt their authority– and then determine whether those neural natural kinds exist inside [cognitive] modules. If they do, there are conscious within-module representations; if they don’t, there are not. But should we include the machinery underlying reportability within the natural kinds in the clear cases? Apparently, in order to decide whether cognitively inaccessible and therefore unreportable representations inside modules are phenomenally conscious, we have to have decided already whether phenomenal consciousness includes the cognitive accessibility underlying reportability. So it looks like the inquiry leads in a circle.

In the case of our parable, this quote would read as follows:

Determine the natural kind (Putnam 1975; Quine 1969) that constitutes the human-activity basis of actual research in completely clear cases – cases in which research papers are presented at a conference and widely shared– and then determine whether those human-activity natural kinds exist when people privately make discoveries and write drafts of their findings. If they do, there is actual research when first writing a paper; if they don’t, there is not. But should we include the conference presentation within the natural kinds in the clear cases? Apparently, in order to decide whether never-published physics papers are "actual research", we have to have decided already whether "actual research" includes the conference presentation. So it looks like the inquiry leads in a circle.

To me, the answer seems clear: "actual research" is not a natural kind, which makes this discussion unhelpful. But Block is, as far as I can tell, is a phenomenal realist. Block (2002), p. 392: "Phenomenal realism is metaphysical realism about consciousness and thus allows the possibility that there may be facts about the distribution of consciousness which are not accessible to us even though the relevant functional, cognitive, and representational facts are accessible." Block (2007) says that "Presumably there is a fact of the matter" about whether "the unreportable representations inside [cognitive] modules" are "phenomenally conscious" (p. 481). This is Block's core mistake.

Some commentators agree with me that we may do best to abandon talk about "phenomenal consciousness". Dennett (1995), commenting on an earlier article by Block, suggests that we reject "qualia" and that "Block has done my theory a fine service: nothing could make my admittedly counterintuitive starting point easier to swallow than Block's involuntary demonstration of the pitfalls one must encounter if one turns one's back on it and tries to take his purported distinction [between phenomenal and mere access consciousness] seriously." Similarly, heated debates about whether unpublished physics papers are "actual research" may show the pitfalls one must encounter if one takes the distinction between "actual research" vs. mere conference presentations seriously.

McDermott (2007) also supports a eliminativist-type view (p. 518):

Assuming our understanding of the brain continues to advance, we will at some point have a computational theory of how access consciousness works. Block’s supposed additional kind of consciousness will not appear in this theory, and continued belief in it will be difficult to sustain. [...]

The computational explanation of how information flows in order to enable subjects to report a row of Sperling’s (1960) array after hearing a tone will of course not refer to anything like phenomenology, but only to neural structures playing the role of buffers and the like.

Replying to McDermott (2007), Block (2007) asks why we can't reduce phenomenal consciousness rather than replacing it, in a similar way as heat is reduced to "molecular kinetic energy" (p. 542). I would respond that reducing and replacing amount to the same thing, but in cases where the concept doesn't have a single, clear referent—which I suspect is the case for phenomenal consciousness and "actual research"—abandoning the concept may be the least confusing option.

Focusing on the moral question

While debates over phenomenal overflow don't pose any deep metaphysical or epistemic puzzles, they do raise an important moral question: what kinds/stages of brain processing do we morally care about? Block (2007) mentions (p. 484) the "practical and moral issue having to do with assessing the value of the lives of persons who are in persistent vegetative states. Many people feel that the lives of patients in the persistent vegetative state are not worth living. But do these patients have experiences that they do not have cognitive access to?" More important in quantitative terms are questions about the moral importance of non-human animal mentation. Even if we dispense with "consciousness" terminology and focus on specific brain algorithms, we still have to answer the question: which of those computations do we care about?

Fri Tanke (2017) includes the following exchange between Nick Bostrom and Daniel Dennett starting at 55m31s. I like Dennett's answer.

Bostrom: At what point in the phylogenetic ladder is there some degree of consciousness that gives us moral reasons to treat the thing one way or another for its own sake?

Dennett: That question, which is behind a great deal of the theorizing and the phony theorizing about consciousness, the question about where do the moral obligations come in, is a serious moral question. It's a serious political question. And the idea that science is going to show you where to draw the line is just not on the cards. There's not going to be, in that spectrum of cases, a pure scientific answer.

My previous writings on consciousness have been criticized for occasionally interchanging

- consciousness as a scientific concept with

- consciousness as "what brain processes do I morally care about?"

Perhaps in a nod to me, Muehlhauser (2017) says in his treatise on consciousness: "I do not define consciousness as 'cognitive processes I morally care about,' as that blends together scientific explanation and moral judgment [...] in a way can be confusing to disentangle and interpret."

This is a reasonable viewpoint. I guess my sentiment is that there are so many conflicting definitions of consciousness even as a scientific concept that the word is still extremely confusing even in that context. I'm very skeptical that there's a single "natural kind" definition for scientific consciousness that different parties would converge upon. It seems potentially more fruitful to downplay talk of "consciousness" and skip directly to the "what I care about" question. (Of course, I sometimes define "consciousness" as "what I, as a sentiocentrist, morally care about"b in order to make my views about sentience more readily explainable without a lot of background exposition. However, doing this causes the confusion to persist.)

Muehlhauser (2017) seems to agree with the long-run project of replacing talk of "consciousness" with more precise statements:

As the scientific study of “consciousness” proceeds, I expect our naive concept of consciousness to break down into a variety of different capacities, dispositions, representations, and so on, each of which will vary along many different dimensions in different beings. As that happens, we’ll be better able to talk about which features we morally care about and why, and there won’t be much utility to arguing about “where to draw the line” between which beings and processes are and aren’t “conscious.”

Footnotes

- The linked page says "please do not quote from this version", but I don't have access to the final published text. (back)

- One might wonder about a circularity like the following:

Sentiocentrist: "I care about sentience."

Other person: "Ok, what's sentience?"

Sentiocentrist: "Sentience is what I care about."

Other person: "So you're saying you care about what you care about."For me, the resolution of this apparent paradox may be that I start with things in the neighborhood of "mental processes" and then think about which of those move me emotionally and which ones seem kinda like the things I naively call emotional subjective experiences in myself. So start with a vague definition of sentience and filter it through moral concern to get a refined definition.

Put another way, a sentiocentrist is someone who identifies with the overall spirit of sentiocentrism, and then particular judgment calls regarding moral status made within that mindset can count as more precise definitions of sentience.

Analogously, an organization might have the overall mission to "help homeless people", but what exactly does that mean? A more precise definition of "helping the homeless" could be "whatever specific things the anti-homelessness charity does to advance it's mission". We can generate a similar apparent circularity here:

Anti-homelessness worker: "I work to help the homeless."

Other person: "Ok, what does that involve?"

Anti-homelessness worker: "Helping the homeless involves doing the specific tasks that I work on."

Other person: "So you're saying you work to do the specific tasks that you work on."This is not really circular as long as the specific tasks the anti-homelessness worker works on are grounded in the overall spirit of reducing homelessness. (back)