Summary

Many seeming puzzles in philosophy stem from platonism and dualism. These fundamental illusions are like Capgras syndrome in that they persist in spite of no rational justification. They play central roles in confusions about consciousness, spiritual realms, free will, moral realism, and mathematical truth. Physicalist monism dissolves these conundrums by postulating that there is just physics, and what we think of as platonic forms are merely concepts—"clusters in thingspace"—that our material minds use to categorize and predict physical processes.

Contents

Epigraphs

Of course, consciousness does seem to make a difference from a first-person perspective. So does God, the soul, and contracausal freedom. Why are we obliged to take these seemings seriously? They - the ideas, beliefs, introspections, phenomenal reports - can be accounted for in terms of physical/functional processes. If these alone are enough to explain first-person appearances, why infer anything more?

You know that we are living in a material world

And I am a material girl.

Introduction

We naturally have dualist intuitions in many domains:

- Dualism on consciousness: Yes, we have neurons and synapses, but it feels like there must be "something more" to my subjective experience than matter moving around.

- Spiritualism: Yes, the world operates according to physics, but there must be some additional spiritual force that animates it and gives it meaning.

- Libertarian free will: Yes, either my actions are determined or else random, but it feels like there's some extra "agency" property that I have that somehow gives me libertarian free will.

- Moral realism: Yes, I don't like slavery, but there has to be something more—some eternal "truth" of the matter as to how slavery is objectively wrong.

- Mathematical platonism: Yes, these sets and numbers that I'm manipulating are useful for predictions and organizing thoughts, but there must be some additional sense in which they "exist" in a platonic realm of perfect mathematical forms.

There are many flavors of dualism, and I won't explore the intricacies here, but what I mean by the term is this sense that "there must be something more than mere physical stuff."

The reductionist account

These errors all seem to stem from the difficulty that we humans have with mentally internalizing reductionism. For instance, it feels like the mind is not just a complex pattern of material operations but must be somehow ontologically distinct—in a different category altogether. This resembles Capgras syndrome: Even though all rational evidence and hypothesis simplicity suggest that this other person is your mother, she doesn't feel like your mother, so you insist she's an impostor. Likewise, in the case of dualist thinking, no matter how much we explain everything via physical components, it still feels like the explanation is incomplete.

Eliezer Yudkowsky described this in the case of the question, "If a tree falls in the forest, and no one hears it, does it make a sound?":

[One possible neural account of how this happens is that] there can be a dangling unit in the center of a neural network, which does not correspond to any real thing, or any real property of any real thing, existent anywhere in the real world. [...]

This dangling unit feels like an unresolved question, even after every answerable query is answered. No matter how much anyone proves to you that no difference of anticipated experience depends on the question, you're left wondering: "But does the falling tree really make a sound, or not?"

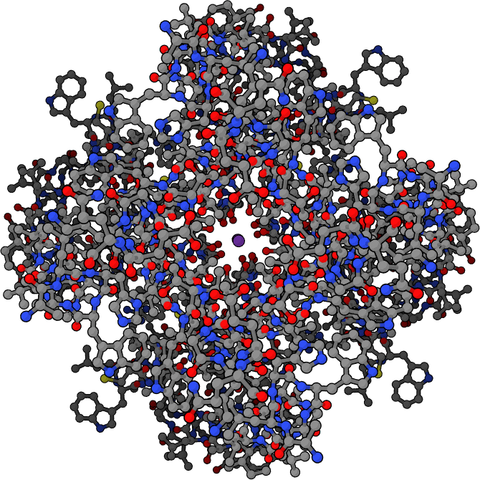

Consciousness, feelings of free choice, moral impulses, and so on all do correspond to real physical processes. In that sense, they exist! But they exist as patterns within physics. They're concepts, what Yudkowsky calls "clusters in thingspace," that we use to organize our thinking about the single, physical substance in which we are embedded. Yudkowsky's post, "Neural Categories," gives a helpful example in which the "central node" in Network 2 represents an abstract property that our brains treat as existing "out there," when in fact it's just an abstraction that our brains create. Extending this model to dualism, the central node corresponds to the dualist substance or property that feels separate from its associated physical parts.

What's wrong with dualism?

The core argument

The fundamental problem with dualism is that it doesn't accomplish anything except to complicate our theories. There are two possibilities.

The first possibility is that the additional substance influences physical events—so-called interactionist dualism. In this case, the substance is not really extra-physical; it's just a different part of physics. The fact that both quarks and gluons exist is not dualism—these are just two types of physical substance. If there were some further, more mysterious force that also affected physical processes, we would say that it was part of physics too. If your dualism invokes a force that affects physics, I wouldn't call that dualism. Let's agree to call it physicalist monism and move on.

The only other possibility is that the additional substance doesn't influence physical events. In this case, what is it supposed to accomplish? Why do I need an entirely separate non-physical thing if it doesn't contribute any extra explanation in the theory? This is called the "interaction problem." You might say that the extra substance explains why we have a sensation of "something more" than physical operations, but that's not right, because your verbal statements that "there's something more" are happening within physics, and if the extra stuff isn't affecting them, then physics by itself accounts for why you feel there's something more. But if physics itself explains why you feel there's something more, then nothing is added by assuming there is something more. That hypothesis is totally useless and amounts to "multiplying entities beyond necessity."

Objection: Brains track truth

Another objection might be as follows: Physical brains tend to feel and reason toward true statements, even those concerning facts outside their direct experience. For instance, we can deduce true statements about galaxies beyond the visible universe. Similarly, that a smart brain comes to believe dualism is, in general, evidence for dualism, because of the truth-tracking abilities of brains.

I admit this is a better argument for dualism. My main reply would be to look more deeply at the specific details of why people believe dualism. Generally those details come down to "a feeling that it must be true." In many physical domains, this is good evidence, because evolved brains are attuned to have accurate intuitions about objects with which the organisms interact. But if the postulated substance never has any interaction with evolved brains, why would our intuitions be well refined there? Our naive intuitions about quantum mechanics are bad, and it's only because we can interact with quantum particles via experiments that we have more correct understandings of the quantum realm. Non-interacting realms of ontology afford no such opportunity for feedback.

In any event, even if the "general truth-tracking-ness of brains" was weak evidence for dualism, Occam's razor should apply a major penalty to the dualism hypothesis due to its complexity.

As neuroscience progresses, we'll develop better models of how dualist beliefs arise, and these will likely show them to be cognitive illusions, similar to optical illusions. Yudkowsky's proposal is one adumbration of what such an explanation might look like. If we could replay evolution (which we should not do for ethical reasons), we might even be able to watch at what point and why these fallacious intuitions emerged.

Objection: Begging the question?

A reader, Daniel Kokotajlo, gave the following reply: "there is not an entirely separate explanation within physics for why you feel these properties exist. Rather, there is an entirely separate explanation within physics for why a certain clump of atoms behaves in a certain way. You are begging the question if you think that clump of atoms is you."

Yes, what I meant was that there's an entirely separate explanation why you say, write, and act like these properties exist, and that your brain has certain activations corresponding to these thoughts. If you think the feeling is separate from all of this, then there would be something left unexplained by physics.

Is there any reason to think moving atoms are a worse explanation of our experiences than non-physical mental stuff? I don't see one. If anything, they're a far better explanation because we can in principle track every cognitive circuit that leads you to say things like "It feels like something to be me" and "I can't believe atoms moving would create this experience." That seems like a perfect candidate for the thing that actually gives rise to your experiences, in contrast to some other thing that for some reason tags along for the ride. So physicalist monism has the same explanatory power as dualism at half the price in complexity.

The basic disagreement here is just one of incredulity: dualists placing "mind stuff" in a different category from "matter stuff" and insist that the matter stuff is not an equally good explanation for phenomenal experience. What seems to be going on is that people have a certain emotional category for "mind stuff," and a different one for "inanimate stuff." Thinking about atoms triggers the "inanimate stuff" category, and then it feels preposterous that inanimate stuff alone could give rise to mind stuff. As an analogy, the gender classifiers in our brains take "has a moustache" as a strong feature for "masculinity," so when we see a girl with a moustache, we get confused. Or take the Müller-Lyer optical illusion: We can measure the two lines till the cows come home, just like we can reason about simplicity of theories all night, and yet we still see the lines as having different lengths, just like people still see consciousness as requiring more than atoms. That said, with practice, both of these illusions can fade.

If you say "Only Thor can explain lightning," then no amount of physics will convince you otherwise, because doing so would always be begging the question, since you can always say, "Yes, but Maxwell's equations don't explain the real lightningness of lightning, just the way it looks. Only Thor explains lightning's true essence." You can always start at a place whose assumptions prevent you from escape. Occam's razor is designed to help prevent us from getting stuck in complicated hypotheses like this.

Example confusions

This section explores specific applications of dualist confusion. The fields that I discuss are complex—consciousness, moral realism, and so on—and many philosophers hold sophisticated stances on these matters that are not undercut simply by the anti-dualist principle. The anti-dualist principle specifically addresses metaphysical claims, not other sorts of claims.

Dualism on consciousness

Cartesian dualism, also known as substance dualism, suggests a different ontological realm for the mind/spirit as separate from the material body. It has plenty of empirical refutations, from physics, neuroscience, brain damage, and so on. But the clearest argument is the one highlighted above: Suppose there were a separate mind stuff apart from the physical world. Does it interact with the physical world? If yes, then it's not really extra-physical. In my view, interactionist dualism is not really dualism but just a bad neuroscience hypothesis. If no, then why do we see such an exquisite correspondence between material operations in the world (e.g., you get hit with a baseball bat) and the mental world (you lose consciousness as a result of the injury)?

One explanation of this correspondence is occasionalism or parallelism, the idea that God or the universe has preordained these two systems to run in perfect synchrony despite not having causal contact. They would be like two clocks that both told the same time because they had been started at the same position even though neither had influence on the other. Needless to say, this violates Occam's razor in a big way. And if we try to invent other hypotheses besides occasionalism to explain the non-physical correspondence, we end up introducing extra machinery of some sort that again is not the simplest explanation.

Cartesian dualism is probably the form that most lay people tend to assume, but among modern philosophers, there's a lot of currency behind a different brand: property dualism, which suggests that mind and matter are both made of the same stuff, but minds have special "mental properties" that are not reducible to physics. Again we have the same fundamental problem of dualism, this time in the realm of properties rather than in the realm of substance. If metaphysically epiphenomenal properties aren't doing anything, there's an entirely separate explanation within physics for why you feel these properties exist, and so postulating that they actually exist explains nothing and merely complicates your theory. Yudkowsky elaborates on this in an amusing diatribe: "Zombies! Zombies?"

Spiritualism

The extension of this argument to belief in non-interacting spirits and deities is sufficiently straightforward so as not to need further elaboration. Of course, physical spirits and deities are not ruled out.

Libertarian free will

Dualism fails because there's no need for the extra-physical stuff. The physical stuff is sufficient, and it's just a quirk of the human brain that it can't place physical operations into the category of mental experience. The same phenomenon happens with free will: It feels like a computer algorithmically selecting among possible future actions does not contain the same libertarian choice that we imagine free will to be. Somehow it feels better, in the minds of certain philosophers, to have a mysterious freedom property that we don't place in the same category as material operations. Of course, if we do have such a property, either it influences our actions in a deterministic way, in which case it's not libertarian freedom, or it influences our actions in a random way, in which case "we" are not really making a free choice either.

Compatibilism on free will is very much like reductionism on consciousness: In both cases, people have strong intuitions that the materialist picture is missing something, and in both cases, we can see logically that the physical operations alone are doing all the needed work. We do in fact have free will, just like we do in fact have consciousness. It's just not a ghost-like force the way we naively envision it.

Moral realism

Note: In this section I'm speaking loosely about a common layperson understanding of moral realism, rather than about specific philosophical understandings of the term.

Some moral realists don't want to acknowledge that moral feelings are mechanical impulses of material organisms and so postulate some additional "objective truth" property of the universe that somehow bears on morality. Like with a dualistic soul, this objective moral truth violates Occam's razor, and beyond that, it's unexplained why we would want to care about what the objective truth was. What if the objective truth commanded us to kick squirrels just to cause them pain?

In general, philosophical "properties"—whether the property of consciousness or the property of rightness—are red flags. They suggest a platonic confusion, as if there's some separate ontological realm of property labels that exists apart from the material world. Just as people say "This action has the property of being moral" in metaphysical Moral Realism, I could equally say "This song has the property of being music" and thereby assert Music Realism, or that "This collection of wood parts has the property of being a table" and assert Table Realism. Or for that matter, assert that "This shape with three sides has the property of being a triangle" and assert Triangle Realism. For more on philosophy of mathematics, see the next section.

There are perfectly sensible meanings of moral realism, such as the suggestion that certain norms tend to be convergent across human societies due to the evolutionary fitness landscape, or that certain attractors in moral meme-space are converged upon more often than others. Our moral views are certainly modified by the environment, selection pressures, and our cognitive architectures. But sometimes this alone isn't satisfactory for realists, and they seek "something more," perhaps in a metaphysically separate realm of eternal truths. The latter is the stance against which the anti-dualism principle has force.

One reader compared my view to Mackie's argument from queerness. I largely agree with Mackie, but it's not just about moral entities being strange; it's that they violate Occam's razor by adding complexity without explaining anything. Non-interacting things don't explain why you feel moral truth exists, so there must be a separate physical reason why you feel this way. People might say, "But I just know moral truth exists; this is all the proof required." In that case, we get into basically a theological debate where one side has faith that the other doesn't. Replace "moral truth" with "God," and many of the arguments look roughly the same.

In fact, moral realism is similar to theism in many ways. Like religious devotion or nationalism in the modern era, moral realism is a motivational force that induces people to sacrifice for the "greater good"—whether that be God, the nation, or "moral rightness" in the abstract. These are emotional feelings that glue societies together and perpetuate norms of fair play and non-selfishness. In that sense, they arguably all served useful functions in the past and perhaps continue to do so for many people in the present. Alas, all of these forms of ingroup loyalty typically also come with outgroup hostility—against those who believe in the wrong God, fight for the wrong country, or advance the wrong moral values. When you believe you are "right," it opens the door to believing others are "wrong."

Like religion, moral realism is a very persuasive meme, and perhaps it even taps into similar brain circuits. In the case of divine-command theory, we even see the two concepts blending. It's much more persuasive to tell someone, "Do X because God says so" or "Do X because it's the moral truth" rather than "Do X because I'd like it if you did X, and doing X would be consistent with social norms that in the long run would lead our tribe to be mostly better off." Religion, nationalism, moral truth, and so on are hacks of memetic evolution to produce group cooperation against our background tendencies of selfishness before we had sufficient understanding and institutions to produce such cooperation by other means.

Mathematical platonism

Stephen Hawking asked the famous question:

Even if there is only one possible unified theory, it is just a set of rules and equations. What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?

Relatedly, why is there such an exquisite correspondence between material stuff and the realm of math? This could be seen as resembling the paradox of occasionalism: There's a universe, and then there's this separate realm of eternal mathematical truths, and why are the two operating in perfect synchrony if they're not interacting?a It seems like we need to either throw out the universe or throw out math as a separate domain of ontology.

Max Tegmark's answer is the former: There is no separate universe stuff; there is only math. Yudkowsky seems to agree:

Back when the Greek philosophers were debating what this "real world" thingy might be made of, there were many positions. Heraclitus said, "All is fire." Thales said, "All is water." Pythagoras said, "All is number."

Score: Heraclitus 0 Thales 0 Pythagoras 1

I incline more toward throwing out mathematical idealism rather than physics. What does it mean to say "the universe is made of math"? That seems to reify math as some sort of platonic domain. I may prefer instead to say something like the following: There is universe-stuff out there, and empirically when we apply certain axioms and logic manipulations, we can predict how it will behave. Math then is seen as a tool that our brains use, just like vision or language or a baking recipe. It's partly learned through experience and partly hard-wired into our neural processing by evolution. Working with mathematical symbols in particular ways allows us to organize and quantify relationships we observe. Pure mathematics then consists in applying these symbol manipulations in further realms, much like fiction writing consists in using words that refer to concrete objects in the world to create novel combinations that exist in our imaginations. Yet somehow linguistic platonism—the idea that fictional stories "exist out there"—seems less prevalent than mathematical platonism.

I haven't studied philosophy of mathematics enough to have a favorite position, but a few that seem attractive include

- Haskell Curry's formalism: Math is the study of formal, syntactical systems, which lack any "objective" interpretation. "Relative to a formal system, one can say that a statement is true if and only if it is derivable in the system." Any formal system is equally valid, but we prefer some over others because they're more useful.

- Fictionalism: "mathematics is a reliable process whose physical applications are all true, even though its own statements are false."

- Embodied mind theories: "mathematical thought is a natural outgrowth of the human cognitive apparatus which finds itself in our physical universe. [...] the physical universe can thus be seen as the ultimate foundation of mathematics: it guided the evolution of the brain and later determined which questions this brain would find worthy of investigation. [...] Embodied mind theorists thus explain the effectiveness of mathematics—mathematics was constructed by the brain in order to be effective in this universe."

These kinds of views explain math in physical terms in a very similar way as we explained qualia, moral truth, and so on in physical terms: as ways the universe tends to behave, patterns in physics, whirlpools in material reality.  Just as psychology is a higher-level language that describes emergent behavior of smaller-scale cells, and cell biology is a higher-level language that describes emergent behavior of smaller-scale molecules, etc., so too mathematics embodies patterns in the universe that can be modeled using their own language. Math is, as it were, a crude simulation of the universe. Rather than reducing physics to math—whatever that means—this approach reduces math as being an emergent property of physics. (By "property" here I mean "something reducible to" rather than "something existing in a separate realm.")

Just as psychology is a higher-level language that describes emergent behavior of smaller-scale cells, and cell biology is a higher-level language that describes emergent behavior of smaller-scale molecules, etc., so too mathematics embodies patterns in the universe that can be modeled using their own language. Math is, as it were, a crude simulation of the universe. Rather than reducing physics to math—whatever that means—this approach reduces math as being an emergent property of physics. (By "property" here I mean "something reducible to" rather than "something existing in a separate realm.")

That said, I don't really have a strong preference what you call the ontological primitive; if you want to call elementary strings and branes "math," that's fine with me. Then everything would reduce to math. I prefer "material stuff" because it feels more intuitive to me to think about globs of stuff moving around obeying certain relationships. Math is then a language that we use to describe this stuff, just like we use words. My position is like saying "This thing exists that we call a 'dog' and makes noises that we call 'barking,'" instead of the Tegmarkian approach, "Dogs exist and have the feature that they bark, which is a kind of noise-making process." Same statement, just a different way of conceptualizing it.b

Physics tells us that stuff obeys certain relationships. Math tells us that sets obey certain relationships. What those relationships are in our universe always needs to be empirically determined. As Einstein said, "As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality" (at least not in our universe—maybe they do somewhere else in a modal-realism multiverse).

"Sets" are not the obvious ontological primitive because the mathematics used in science can be done without set theory. See "Is Set Theory Indispensable?" by Nik Weaver. If you can do math without sets, it seems odd to suggest that sets themselves are ontologically primitive. Rather, there is an ontological primitive thing out there, and sets are one way to model it.

Viewing logic as merely a technology for modeling and prediction makes logical paradoxes and Gödel's theorems seem less metaphysically mysterious: Rather than referring to eternal truths in some external metaphysical realm, they just describe pitfalls and limits of our tools. They're not fundamentally more mysterious than, say, bounds on the ability of computers to store data or calculate answers efficiently.

Mathematical fictionalism and cognitive-science views avoid various issues with platonist mathematics:

- Benacerraf's identification problem: That there are many ways to reduce mathematical objects is fine, because we only need mathematical fictions for instrumental purposes, and human minds have many conceptual tools by which to imagine a concept.

- Benacerraf's epistemological problem: Since mathematical objects are not real things existing "out there", we have no puzzle about how we come to know them. Our brains are evolved to conceptualize structures, and these structures can be combined in many complex ways. This is true just as much for fiction novels as for mathematics.

- Unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics: In platonism, the exquisite correspondence between mathematical objects and physical phenomena is mysterious. In contrast, if we see mathematics as a byproduct of brain structures that evolved to cope with the world, it's unsurprising that mathematics captures at least everyday physical phenomena, because it was designed to do so. It does remain a coincidence that humans' basic conceptual frameworks can be extended in ways that helpfully model realms of physics outside of ordinary experience (e.g., who would have guessed that complex numbers would be indispensable for quantum mechanics?), but maybe it's not that much of a coincidence, because Occam's razor should incline us to imagine that the universe can be modeled with just a few basic axioms. Of course, this argument pushes back some of the explanatory work onto Occam's razor, but that's arguably a separate discussion from philosophy of mathematics.

Sometimes mathematical platonism is defended on the grounds of confirmation holism: We need math for our best scientific theories, and theories come in whole bunches. We can't strip out the math separate from the science. While I appreciate confirmation holism, I think it's confused to claim that it justifies mathematical platonism. When math is used in science, we don't mean to imply that physical stuff exists and mathematical stuff exists. Rather, we mean to say that physical stuff exists and can be described in the language of math. Analogously, suppose we describe clouds by pictures or the Earth's water cycle by arrows between the ocean, the sky, and rivers. These pictures and arrows are tools that help us talk about the underlying physics. They don't imply that cloud pictures are ontologically fundamental or that arrows "actually exist" in some platonic realm.

Physicalist monism

In summary, we have a thorough reduction of ontology to just one level of reality—physical stuff.

- What is a table? It's a category into which we classify physical objects that tend to have legs, on which people tend to eat dinner, and that are often made of wood or metal.

- What is "green"? It labels a cluster of the appearance of certain objects, such as summer leaves, grass, and Christmas trees. Empirically it corresponds to light at about 510 nm in wavelength.

- What is consciousness? It's a category into which we classify physical operations by minds when they aggregate, broadcast, and manipulate information in certain ways.

- What is free will? It's a sensation we feel when choosing. It reflects a recognition that our decision procedure has multiple options that it's evaluating and for which different activations in the brain are being generated.

- What is truth? Our brains have epistemological systems that classify some statements as "true" and others as "false." We have additional machinery that allows us to manipulate these statements (using logic) in ways such that, when we act upon the statements expressed by the manipulated versions (deduced conclusions), we tend to achieve successful predictions of observed outcomes. Because of the utility of these systems, evolution has built in this logical circuitry to our brains such that the truths feel a priori.

- What is mathematics? Given certain generalized statements (axioms) that make sense to our brains based on hard-wiring and environmental inputs, we manipulate these statements according to logical rules that our brain finds intuitive in order to arrive at further statements. We can construct more and more complex arrangements of these relationships, and the statements so derived tend to be useful in many domains, such as explaining physical phenomena. We can even apply these rules to completely unfamiliar domains like higher-order infinities, thereby creating beautiful tales of mathematical fiction, which may prove useful at some point in the future.

- What is moral truth? We have feelings about how we'd like the world to be, and there are norms society expects us to follow. We describe them using predicate statements and manipulate them using logical rules. Insofar as we feel motivated by the original statements, we also tend to feel motivated by the logically derived statements. Sometimes we derive conclusions that we don't like and then seek to resolve the dissonance.

Ontology vs. pragmatism

I guess my views fall somewhere near the empiricist / pragmatist schools of philosophy. We use science because it works. We use math and logic because they work. We use Occam's razor and favor elegant theories because they tend to serve us well. There are plenty of seemingly a priori truths that don't work, like the Newtonian conception of time as a universal absolute or Euclidean geometry as the obviously correct view of space. If calculus stopped predicting any physical or social observations, then so much the worse for calculus, no matter how intuitive it might seem. We could relegate it to the realm of "fun fictions to think about that don't actually help in applied settings." This is how most people live most of their lives, except in certain domains like religion and philosophy. People (and animals in general) intuitively focus on what works in their experience, and theories are only as good as how well they encapsulate this.

What is "real"?

But then what is the place of my physicalist ontology? That seems like a grand, metaphysical claim that potentially goes beyond pragmatic justification? Not really. My physicalism is contingent too and could change with new insights. It's not fundamentally different from more "scientific" theories, except that it's more abstract and extrapolated. It's a natural extension of many tools that scientists use successfully. It helps conceptualize and organize phenomena in sensible ways, just like the naive picture I have of an atom as a dot with eight electron slots in its outer orbital is a way to help me conceptualize chemistry.

But is this physicalist ontology "real"? Well, it seems like a robust, elegant picture that has predictive power in many domains. This is as good a definition of "real" as I can think of. What else should "real" mean? If it meant "true in some perfect platonic realm," then we get into the pitfalls of platonism once more.

Causation

Maybe we could attempt a similar maneuver in explaining the difference between correlation and causation. In a Philosophy 132 lecture (spring 2010, lecture 30), John Searle points out that day follows night, but this doesn't mean night causes day; rather, the cause is the Earth's rotation. Searle claims that causation is more than just correlation.

Here's one possible account of causation as a certain kind of correlation. I think it's basically the same as Judea Pearl's, but I'm not familiar enough with his views to say for sure. If we knew nothing about astronomy, we might construct a very simple model in which night did cause day. Here, "causation" is a property we read out from our model, presumably in part based on conditional dependencies. Then, as we learn more, we need to expand our model to accommodate the new data. Within our expanded model, the astronomical picture looks different. Now our model contains a rotating Earth for other reasons, and that seems like it explains the correlation of day following night. So we no longer need to say that day causes night. And we can imagine cases where our original causal explanation would be falsified, such as if the Earth's rotation stopped. Then, so the new model predicts, night would cause day vastly more slowly (only once per year when the Earth was on the other side of the sun).

Like with asking whether atoms are "real", when we inquire whether a process is really a "cause", we can interpret this as asking whether our attribution of causation to that process will be robust against further updates to our model. In fact, this is similar to what's done in multivariate regression: Statisticians attempt to infer causation from correlations when the regression coefficient of a particular variable remains robustly nonzero across many model types that contain other possible explanatory variables.

What is true causation?

The preceding discussion helps explain what it looks like for us to attribute causation based on our limited understanding of the multiverse. But if we had a complete physical model of the multiverse (e.g., a giant computer program that specified how the multiverse evolved), then we could define whether X actually causes Y as follows: Change the program to remove X in some way and see if Y still happens. If not, then X was at least one of the causes of Y. This is called "but-for" causation in a legal context.

We can see that this definition avoids capturing mere correlations. For example, suppose there's a correlation but not causation between race and IQ—that, say, African Americans on average score lower on IQ tests. Does having African American genes cause lower average IQ? To see this, we could change the computer program that runs our multiverse to replace the genes of thousands of African Americans with the genes of white Americans (maybe except for skin pigmentation, so that the black parents wouldn't be weirded-out by having white kids) but keep the parents and socioeconomic details of those people's lives constant. If doing this didn't change the average IQ of those people, then African American genes weren't a cause of the IQ difference.

This definition of causation removes all metaphysical weirdness regarding what's actually a cause or not. Causation is just a property that we attribute to the program that runs the universe based on imagining counterfactual ways the program could have been run and what outputs those counterfactual programs would have had.

The idea that controlled experiments are the gold standard for establishing causation also relies on this definition. Causation can be shown if manipulating one thing and keeping everything else constant changes the result. If we had the source code for the multiverse, we could (if there weren't ethical constraints against running multiverse simulations containing conscious suffering) manipulate any arbitrary pieces of code and thus conduct "controlled experiments" on anything.

Objections

Alvin Plantinga's evolutionary argument against naturalism alleges that mere pragmatism is not enough to ensure that evolved beliefs track the truth. It could very well be that we have intuitions which track a convenient falsehood that helps with survival at least as well as knowing the truth would aid survival. Plantinga proffers a fanciful example of a person Paul running away from tigers, but we can see a real instance of this with our naive view of physics: We perceive the world as exhibiting Newtonian dynamics, based on Euclidean space, in a classical framework without quantum weirdness, in a universe of 3+1 dimensions. Our raw perception knows nothing of quarks or superstrings. So yes, in some sense Plantinga is right: Our evolved intuitions do not fully track the truth. But we can do experiments to probe the world in ways previously inaccessible to our ancestors, and the results we observe illustrate problems with our naive intuitions. Over time, our beliefs become at least more aligned with the underlying stuff of the universe. And if there are truths we'll never be able to access, well, that's life. We can't expect perfection but just do the best we can.

One might say that if we have no access to realms of reality that we can't manipulate, then who cares about them at all? In one sense this is right, but it ignores the fact that life is not just about making predictions. I also have goals in the world that I understand via describing them in the language of my ontology. My utility function cares about phenomena like suffering and consciousness, which are objects within my world model that are more than predictions of future observations. I carve out these features of my conceptual framework as things that I manipulate, treating them as "objects in the world." Ultimately I am just interfacing with input observations being processed by neural machinery that has been constructed with certain prior biases, but within my internal model, these things are "real objects," and I care about and act on them as such. This is not really a surprising viewpoint to hold. It adds up to the normality of our ordinary lives and just helps clarify what it is we're doing when we hold beliefs, act, have desires, and so on.

An example of where ontological commitments matter is with the question of other universes in the multiverse. Some claim that if other universes are not accessible to us, we may as well regard them as not existing, and so presumably we wouldn't care about them. But this would be akin to saying that because I'll never visit Africa, I can assume Africa doesn't exist. Africa and other universes are straightforward extrapolations of robust scientific theories, and so it makes sense to probabilistically assume they exist for purposes of my utility function. In contrast, immaterial souls contained within rocks are not straightforward extensions of robust scientific theories, so my probability for them is quite small. Basically, X exists with probability p if a probability-weighted fraction p of my predictive hypotheses for the multiverse contain X. Then my actions express caring about X with weight p. This whole operation happens within physics and doesn't require some external platonic realm that I tap into when I do these calculations.

I like this quote from David Deutsch: "To say that prediction is the purpose of a scientific theory is to confuse means with ends. It is like saying that the purpose of a spaceship is to burn fuel."

Comparison with indispensability argument

The previous paragraph about multiverses sounds like the Quine-Putnam indispensability argument for mathematical platonism. But I said above that I rejected platonism. So why I do accept that other universes exist if they're essential to our best scientific theories?

The reason is that postulating mathematical entities as things doesn't serve any purpose. Suppose I have two pennies. I can describe this by physical statements about there being a penny here and a penny there, and I use the number "2" as a way to conceptualize and manipulate the physical state of affairs. It wouldn't help for "2" to be a "real thing" in some platonic realm, because then we'd have to ask what the relationship is between "2" in that world and the structural property of 2 as a way to describe physical configurations. Why should a concrete thing also be a conceptual structure that describes other things? Why not just use conceptual structures as conceptual structures without hypostatizing them?

The situation is different for other universes, because these are not structures over physical entities; they are actual physical entities. A universe is something that exists, while a number is a way to describe what exists, in a similar way as a words do.

A matter of faith

Daniel Kokotajlo replied to this piece with the following comment:

It seems like you forget why we believe in physical systems and events in the first place. Your ontology may be pretty, but your epistemology is ugly as hell. And if we are willing to have ugly epistemologies, then I can top yours easily: Nihilism. Occam's razor prefers nihilism to all other theories. You protest that nihilism doesn't explain our experiences? Well, that's exactly what the dualists say about your theory.

It all comes down to what counts as "explaining our experiences." Different theories about that will yield different theories about consciousness, personhood, metaphysics, etc.

Yes, I like to say that I have faith in one thing: The existence of physics. Dualists have faith in two things: Physics and extra-physical mind stuff. Non-physicalist theists have faith in three things: Those two plus God / Holy Spirit / gods / etc. Or maybe many things if you include angels and demons and all the rest.

The presuppositionalists are right that there are no neutral assumptions to ground epistemology. Fundamentally it comes down to a matter of faith. Some people feel their experiences can't be explained without appeal to a Heavenly Father, and they insist that no amount of these other ontological components can make up for Him. They can feel divine presence, and how could this fundamental perception be in error?

People sometimes also express more abnormal convictions. For instance, Michael Graziano reports of a patient who "thought that he had a squirrel in his head. Odd delusions of this nature do occur, and this patient was adamant about the squirrel. When told that a cranial rodent was illogical and incompatible with physics, he agreed, but then went on to note that logic and physics cannot account for everything in the universe."

At bottom, I can't argue with someone who holds these positions. Likewise, some people feel their experiences can't be explained without appeal to non-physical mind stuff. I similarly can't argue other than to express my own disbelief and wave my hands at Occam's razor and the coherent beauty of physicalist monism.

The nihilist is indeed taking the most elegant ontological approach, and I admire that. I happen to be a Believer in one ontological realm, physics, rather than no ontological realms. I have a friend who is a true nihilist, and I respect her view. It's much more plausible to me than dualism. But I remain a Man of Faith who believes in 1 and not 0 ontological primitives.

Footnotes

- Gary Drescher discusses similar ideas in Ch. 8 of Good and Real. (back)

- Update, Jun. 2015: I'm no longer sure this paragraph is accurate. I think part of the appeal of a "universe is math" approach is that it potentially allows for eliminating the question of what it means for a universe to be actual rather than merely possible. One can say that "actual" doesn't mean anything, and everything is just logical possibility. Then we also don't need a notion of what "existence" means, since nothing "exists" in the sense of having ontological fire in it. I think this is different from Tegmark's position, which as far as I can tell seems closer to "mathematical platonism without non-mathematical reality".

Basically, there seem to be three possible views to choose from:

- Physics is ontological "fire", and it can be described by math.

- Physics is math, and math has an ontological "fire" to it.

- Physics is math, and there is no ontological "fire".