Summary

This piece compiles advice for students interested in earning to give, including tips on high school, college, and working at a job. My discussion here is by no means comprehensive, and I encourage you to consult many other resources on these topics.

See also "Employers with Huge Matching-Donations Limits".

Contents

- Summary

- Other resources

- Caveat

- Importance of this topic

- High school

- College selection

- College majors/minors

- Internships and externships

- Networking

- Career selection

- How to determine salaries in a field?

- Automation trends make tech look promising

- In general: Don't get a PhD

- Interview prep

- Negotiating offers

- During your job

- Interviewing with other companies

- Acknowledgments

- See also

- Appendix: Comparing software industry vs. quant hedge funds

- Footnotes

Other resources

- 80,000 Hours provides comprehensive suggestions on choosing a career for maximal altruistic impact.

- "Career Advice for High-Impact Activism" by Nick Cooney.

- Cognito Mentoring has tips for gifted young people on high school, college, careers, and more. See, for instance, "Career options".

- Vault guides provide excellent overviews of various careers, including sample "day in the life" sketches. The "career services" department at your college may have them, and if not, it's worth the money to buy them or sign up for Gold membership.

- GlassDoor is an excellent resource for salary statistics and company reviews.

- Monster.co.uk Career Advice podcast.

Caveat

My information is USA-centric, though I expect that similar trends mostly apply in other countries. Also, I did most of my career research during 2006-2008, so some details may have shifted since then, but by and large I expect that the current career landscape looks similar.

Importance of this topic

I see career choice as one of the biggest altruistic projects in life. Some other essential altruistic activities are (1) learning how the universe works, (2) searching your soul to determine what you value, and (3) figuring out how strategically to push on those values (e.g., where to donate, what institutions to build, what ideas to promote, etc.).

I like this quote from Holden Karnofsky about the importance of career:

How much time is it worth spending on choosing a career? Should you reevaluate at certain points? I've always been like completely obsessive about career. [...]

I tend to think that's probably a good thing not a bad thing. I just think career is so important. It affects your happiness and what you get out of life and who you meet and what you become good at and what impact do you have in the world and it really is where most of your waking hours are going to go.

This is the basis of the name "80,000 Hours": 40 hours per week times 50 weeks per year times 40 years of working. (Of course, depending on what field you enter, it might be more like 120,000 hours.)

The best career for you varies (within limits) based on your personality and skills, so a reasonable amount of individualized research is required. This differs from other domains where you can trust the mainstream consensus on a topic without investigating it further. There is no single best career for all people.

High school

You've probably heard a lot of advice on how to impress colleges from your teachers and guidance counselors. You might also search the Internet for a few more articles on the topic. Some of the biggest points are to take challenging classes, get good grades, participate in extracurricular activities, find something impressive to do over your summers (e.g., an internship), and take some practice SATs so that you'll be used to the format and time constraints of the test.

It's never too early to begin researching careers, because your choice of college major should be informed by career plans. Unfortunately, no formal education ever walks you through this process in much detail. One of the most important decisions of your life—what career to pursue—is left to you as a free-time activity. You could start with standard, high-level career books or websites and then focus on particular candidate careers in more depth.

Some other useful skills that school doesn't teach you include how to wear a suit, how to tie a tie, and table manners if you're taken out to lunch during an interview. Also make sure to bring a suit/tie (or the female equivalent) to college in case you have an interview or visit an employer.

Some other useful skills that school doesn't teach you include how to wear a suit, how to tie a tie, and table manners if you're taken out to lunch during an interview. Also make sure to bring a suit/tie (or the female equivalent) to college in case you have an interview or visit an employer.

College selection

I recommend choosing the most prestigious college you can get into. The purpose of college is to impress people. Under their veneers, colleges often aren't that different, so you may as well pick one that looks good.

In the US, probably Harvard and Princeton top the list in terms of prestige; in the UK, Cambridge and Oxford. Even if it costs a lot of extra money to attend a prestigious college compared with a state university, go to the prestigious school. Unless you don't earn to give, you'll more than make up for the price through later earnings. (Note: This claim has been disputed.)

I personally chose a small college, Swarthmore, rather than an Ivy League college because I wanted smaller classes and closer interaction with professors. I probably had a better experience due to Swarthmore's limited size than I would have had at a university, but overall, I wish I had applied to all of Harvard, Princeton, and Yale to see if I could have attended one of them. They have better name recognition than Swarthmore, and having attended an impressive-sounding college is worth a lot of money.

College majors/minors

While there's no one-size-fits-all answer for what to study in college, I think a reasonably robust general recommendation is to major in computer science (CS) and minor in statistics, math, physics, engineering, finance, or business. If you want, you could make CS a minor and a quantitative subject your major, but it's important to at least get several core CS courses under your belt.

When I began college, I kept all options on the table for my major, including history and linguistics. However, a friend told me I should study a hard science because this would allow me to get any job later, and the friend was really right about this. Hard sciences are the master keys to careers—not just quantitative careers, but all careers. At a career fair in 2006, I talked with a representative of a consulting firm, and when I told her I was planning to major in math, she replied: "Oh, we love math majors, because they can think analytically." The "hardness" of a science correlates strongly with the average IQ of its majors, so studying physics or math signals your intelligence to outsiders.

Computer science and statistics are special among the hard sciences because they're the two subjects whose contents are directly applicable in subsequent careers, unless you go into a specialized field like chemical/mechanical/nuclear engineering. (It's not an accident that I majored in computer science and minored in statistics.) Many of the most lucrative jobs require some knowledge of statistics and some knowledge of computer technology—finance, management consulting, actuarial work, entrepreneurship, and obviously software engineering. Investment banks need lots of software developers, and this trend should only amplify as traders are increasingly replaced by machines. Even if you just want a regular investment-banking job, it's plausible to me that a quantitative/programming background will improve your odds of getting a foot in the door on Wall Street, at which point you can move around more easily. If you're not 100% certain about doing finance, computer science will give you an excellent fallback option of working in Silicon Valley.

College is not about studying what's most interesting; it's about signaling your intelligence and skills to future employers. You can (and should) learn philosophy and social sciences in your free time. But having formal qualifications in a hard science opens the most possible doors. Unless you're completely certain you won't ever earn to give, I recommend a hard-sciences major. And if you are completely certain you won't earn to give, I'm not sure college is worth the cost unless it's basically free where you live or completely defrayed by your parents.

Even if you study CS and statistics, very little of what you learn in college will be used in your career. Most skills for most jobs can be picked up on the jobs themselves. College is basically an exercise gym and testing ground to prove your assiduity and acuity.

Internships and externships

The more work experience you have, the more desirable you'll be to employers. So try to get an internship during every summer of college. I found this very difficult after my freshman year, because most employers want rising college seniors. But I managed to get an internship with my Congressman's office in Washington, DC. The next year I applied for lots of finance internships and never got a call back—again because most finance companies want rising seniors. But with enough persistence, I at least got an actuarial internship.

Your internship after your junior year has special significance, because often companies use these as a test run to see if they want to extend a full-time offer for the following year.

In addition to internships, some colleges coordinate externships that allow you to try out a career for just a week. At Swarthmore, these were assigned based on interest (and seniority) rather than qualifications, so they were a helpful way to break the cold-start problem in a field. Presumably you'd be more likely to get an internship in finance if you had an externship in one. Of course, because assignment was based on interest, there was often a low chance of getting any given very desirable externship.

You can also show interest in a career via clubs, like an Investment Club for finance or a Business Club for consulting.

Networking

When applying for internships, don't be discouraged if you send out 10 cover letters without any responses. On the other hand, in addition to dispersing applications to employers you don't know, also use your network to contact an existing employee of the company where you're applying because s/he may pass along your résumé more directly. This can be surprisingly easy if your school has an Alumni Directory that allows you to search alumni by their career fields. Alumni are often eager to talk with current students. Several alumni talked with me on the phone for 30-60 minutes each to give me advice. Many more provided insights by email and offered to pass along my application.

It's hard to overstate the importance of networking, especially when you face the cold-start problem of entering a field without any existing experience in it. Don't be shy about emailing many alumni who work in your field of interest, so long as you're able to take the time to communicate with them. And it doesn't have to be just alumni: Find contacts via friends, Facebook, LinkedIn, specialized industry networking sites, the effective-altruism hub, or even people's own websites. When I was considering applying to Carnegie Mellon University's Machine Learning program, I browsed the profiles of some grad students and emailed them using the contact info on their websites. A few wrote back, and one of them talked with me for 1.5 hours on the phone. Breaking into a network is really easy as long as you're not shy about initiating contact.

It's sometimes claimed that the American Dream is a facade because to get lucrative jobs, you have to know the right people, which only already privileged students can do. In my experience this isn't really true; I think a lot of high-paying jobs are pretty meritocratic. If you're sufficiently dedicated and have at least above-average intelligence, you can network your way into almost any community (except maybe billionaires and celebrities). Networking is easier than ever in the age of online forums, email, and social-networking sites. One reason the American Dream typically doesn't come true is that underprivileged students are often not mentored along the path toward achievement and so may have weaker academic credentials. They also may not know what questions to ask in order to begin learning about high-paying careers. Needing to work long hours to pay for college can also be a significant obstacle. One of the reasons I did academically well in high school was that I didn't work at the sime time, while some of my classmates did shifts at the grocery store or gas station in the evenings. I did work a few hours per week during college, but that was pretty trivial; some students have to work full-time to pay for higher education.

Career selection

The list of possible careers in which to make money is too long to present here, and you'll want to explore many options that are tailored to your interests. Following are a few big-picture observations, mostly based on the research that I did personally during college. I seriously considered entering each of these careers except for (non-software) engineering, law/finance professor, and medicine.

Finance

-

Pros

- Highest expected earnings of any career (except possibly startups) if you work in hedge funds, investment banking, or trading.

- Typically no advanced degree required.

-

Cons

- Extremely long working hours for investment banking. Very high attrition rates, which means many/most entry-level i-bankers don't ever reach the promised land of half-million-dollar annual compensation. For a scary account of life in i-banking, see Monkey Business: Swinging Through the Wall Street Jungle.

- Traders typically only work during (and slightly before and after) market hours, but they work all day long at high intensity. The atmosphere is often extremely aggressive. Gordon Gekko said: "Lunch is for wimps." A real trader I talked to said he did eat lunch, but always at his desk. Business Insider reports that "Lunch breaks are limited to 15 minutes" and "Bathroom breaks are rare unless you really need to go."

Quant developer in finance

-

Pros

- Less stress than i-banking or trading. Typically shorter hours than i-banking.

- Advanced degrees are a bonus but not necessarily required, especially not for programming. Quant jobs may want at least a Master of Quantitative Finance. See Starting Your Career as a Wall Street Quant and Wilmott Forum for more on quant work. My Life as a Quant paints a more biographical portrait of the field.

-

Cons

- It's less lucrative to work in "back office" jobs, because you're further from the trading that makes money. Some quants work in the "front office" on trades, but in that case they have more stress. As a rough approximation, I gather based on Glassdoor and various online discussions that 40-hours-per-week finance programmers earn slightly above $100K/year (possibly less than in Silicon Valley), while those working 60 hours/week or more in high-stress trading roles may earn $200K-400K/year.

Management consulting

-

Pros

- Pretty lucrative, though not as much as finance.

- Provides good career capital and business background. You'd learn more high-level insights about the world than in most jobs.

-

Cons

- Long hours (~60/week?, compared with ~80-100? for i-banking).

- Most consulting jobs require travel most of the time, which means you'll spend most of your days in hotels away from home. (This could be a benefit depending on your preferences.)

- After a few years of consulting as an analyst, you typically need to get a (very expensive) MBA to progress further. (This may also be true for i-banking, by the way.)

Startup founder

-

Pros

- Low/mid chance of making millions, extremely tiny chance of making billions. See "Salary or startup? How do-gooders can gain more from risky careers" and "How much do Y Combinator founders earn?". 2.5% of startups are accepted to Y Combinator, and "Of Y Combinator founders, the top 0.5% have 80% of the total equity".

- According to a friend, if you have startup equity, you can probably(?) donate it and avoid paying federal taxes on all of it, whereas if you earn salary, you have to pay federal income taxes on 50% of it even if you donate all of it.

-

Cons

- Founders often face high stress and long hours.

- Because you're likely to fail, you probably need some personal savings before you can embark on a startup. Many people follow the model of working for a bigger company for a few years, saving up, learning the lay of the tech land, and then jumping ship for a startup, possibly with coworkers.

- If the marginal value of your donated dollars declines sharply, perhaps because you're trying to fund small nonprofits with only so much room for growth, then the expected value of startups is less enticing than a risk-neutral calculation would suggest.

Founder vs. employee

The risk-neutral expected value of founding a startup appears quite high if you're skilled—perhaps several times the risk-neutral expected value of working at a company. Investors want founders to keep a significant share of equity due to principal-agent problems. In contrast, being an employee at a startup seems to offer no real increase in expected earnings over working at a big company, and in fact, my general impression is that bigger companies may even pay better (though there's obviously wide variance). Even early startup employees probably won't get more than 1-5% equity, and that much equity isn't worth very much in expectation. For instance, suppose the startup has a seed-round valuation of $5.3 million. Say you get 2% equity. That equity is worth no more than $5.3 million * .02 = $106K, because you could have bought that much equity as an investor for that price. Moreover, buying equity as an investor is better than earning it as compensation because

- investors typically get preferred stock, which is more valuable than the common stock that employees typically earn

- investors can diversify and thereby reduce much of the idiosyncratic risk that individual startups face

- employee stock vests (typically over four years), so you lose some of it if you switch jobs before vesting is complete; in contrast, investors get all the equity immediately.

Finally, your 2% equity will probably get diluted a lot over the startup's lifetime, perhaps by a factor of ~2 to ~4 times. See also "Trading Salary for Equity: Do the Math" in this piece.

Software developer

-

Pros

- Decent salary ($100K-200K) with much less stress than the above options.

- Can get a high-paying job directly out of college. Starting salaries in software are higher than for almost any other field, which makes this a particularly good option if you plan to earn for only a few years or plan to switch careers.

- Software engineers on the West Coast of the US typically have flexible working hours and dress code. Working from home on occasion is no problem. For these and other reasons, CNNMoney lists "Software Architect" as the best job in America.

- Culture is geeky, friendly, and often positive-sum.

- Work is intellectually interesting and challenging.

- While demand for most other professions will decline with time due to automation, demand for software developers should only increase because software developers are the ones doing the automation.

- Skills are highly transferable, including to finance if you later want to move there.

-

Cons

- Unless you're a top performer at a top software company, my general assumption is that Silicon Valley pays maybe like ~half as much as you would earn doing quantitative programming on Wall Street?

- The social impact of software products seems often net positive in the short term, but because software improvements also speed up artificial general intelligence, the net long-run impact is ambiguous.

Actuary

- Almost the same points as for software developer, except that starting pay is lower and maybe(?) upper-end pay is higher. See "DW Simpson Actuarial Salary Survey". If you plan on an actuarial career, begin taking actuarial exams in college; these will look impressive when you apply for internships, since some other applicants haven't taken any exams yet. You can take the first exam after a course in probability. Make sure to get a study book; you're unlikely to do well if you just wing it.

Engineering besides software

- I haven't studied these options in much depth, but the pros and cons are probably similar as for software developers.

Law firm

-

Pros

- Probably higher pay than software if you graduate from a top law school.

-

Cons

- Opportunity cost plus tuition cost of three years of law school. I tend to advise against law for this reason. It's expensive to change your mind later. Don't go to law school unless you're 105% sure you want to be a lawyer. Books like Don't Go To Law School (Unless) may help with the decision. One L is a famous book about the law-school experience.

- Law typically has long hours (~60/week?), and burnout rates are not low.

- My impression is that legal work may become less lucrative as law is increasingly automated, although I don't know at what pace this will happen. Also, because philosophy majors and other non-quantitative college graduates can become lawyers, it seems theoretically like aspiring lawyers should face steep competition.

Law/finance professor

-

Pros

- Lower stress than working in law or finance directly.

- Pay is still pretty good (~$200K/year?) because these professors could easily go work in law/finance if they wanted.

- Some JD/PhD programs cost less than a simple JD.

-

Cons

- It takes a long time to begin earning (~7 years?). Only pursue one of these options if you're 110% sure you want to stick with it.

Medicine

-

Pros

- Excellent pay ($200K-300K), especially if you're a specialist.

-

Cons

- It takes an extremely long time to become a high-earning doctor. There's a high chance you'll change your mind about careers before you get to that point. Medical school is very intense. Only pursue this option if you're 115% certain of wanting to stick with medicine for many decades. You also need to decide early in your college career because there are many pre-med undergraduate course requirements.

- Reasonably high stress and long hours.

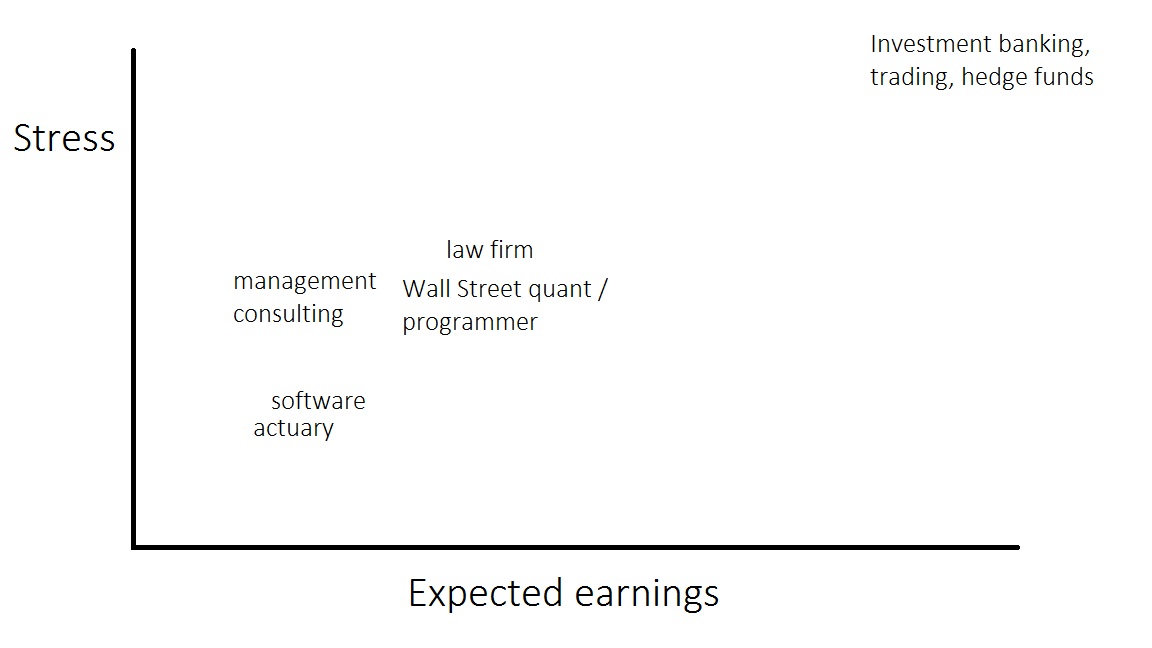

Stress vs. pay

Following is a totally non-rigorous figure that illustrates my rough intuitions about the earning potential and stress levels of some of these careers. The graph is not based on specific data but rather on the accumulation of general impressions I've gotten from reading about these careers over the years. The differences among careers that are close together are not significant—it's just that I couldn't draw the words on top of each other.

You'll probably change your career path

One reason I favor careers that pay off right away is that you're very likely to change your mind about what career you want to pursue, perhaps many times during your life. This consideration favors doing things that are immediately valuable—including both earning money and working for an important charity.

The human instinct to gobble up all the yummy stuff right now rather than saving for the future is an adaptive impulse in the face of high uncertainty. Your career is a matter of high uncertainty. So I think a good heuristic is generally to do the most useful thing you can now and worry about the future later. There are few irrevocable career choices. You can always start over on a different career path if you abandon your current path. In this sense, I place less importance on "career capital" than 80,000 Hours does. I think it's not that hard to break into a different career later in life.

How to determine salaries in a field?

I would use a combination of these approaches:

- Payscale.com and other results from searches, though I don't put too much stock in them.

- I've found GlassDoor.com to be pretty good. At least, it's quite accurate for software-engineering salaries in the US. I don't know how well it handles Wall Street bonuses that represent much of the income of bankers and hedge-fund managers.

- Search for job ads and see what kinds of salaries and bonuses are offered. Google has a special search feature that can come in handy: As an example, {quant $100..200} returns {quant} result pages that contain numbers between $100 and $200.

- Get books targeted toward working in that career. Often these will have salary surveys or at least will quote a few offhand numbers about what you can expect.

- Write to people who work in these industries and ask them for ballpark figures. This will likely be most socially appropriate for recent college grads. Often, just one or two salary data points from someone who you know is at about the same ability level as yourself is better than all the data points in the world from a collection where you don't know who exactly is in the average.

You could attempt present-value calculations based on salary projections, the time delay to enter the career due to education requirements, and how long you might stay in the field. But keep in mind that these will depend on many assumptions and so shouldn't be taken very seriously. I find it reasonably likely you'll switch careers within 5-10 years of starting employment.

Automation trends make tech look promising

Assuming efficient financial markets, the current price of a stock is an unbiased estimator of its future price, minus average returns. In contrast, current earnings in career X are not unbiased estimators of future earnings in career X. The supply of professionals in a career changes slowly over the span of decades, and changes in demand are somewhat predictable in the long run. In particular, it seems likely that on the time scale of decades, jobs vulnerable to automation will pay less. This is often discussed in the popular press as "robots taking our jobs".

I expect that non-programmer financial traders will be mostly replaced within decades. Some predict that a similar fate may befall lawyers and doctors. If you're about to enter a career now, these facts may not be hugely relevant, assuming you don't want to remain in the same career for a long time. But if you're still in high school or considering investing in a protracted and expensive slog through pre-med and med school, these considerations may be more relevant. I doubt automation will happen very quickly for currently prestigious jobs, but I also wouldn't bank on earning high pay as a lawyer or doctor for the next 50 years straight.

Of course, it's well known that tech jobs too can be replaced—if not by computers then by lower-wage workers in China and India. This is true, but historically, wages for top tech talent has remained high and even grown in recent years. Given that demand for software expertise will only increase, it's plausible that high-skilled tech jobs will remain a good bet into the future, unless the supply of qualified talent increases dramatically.

In general: Don't get a PhD

If your goal is to earn money, there are very few cases where a PhD makes sense.

I love academia and research, so during college I sought career possibilities where a PhD would have high payoff. I prepared to apply to machine-learning PhD programs, with the intent of working for a startup after I graduated with my doctorate. Time and time again, people told me to skip the PhD and work directly. I had one friend who thought a PhD would pay off in the long run, but this minority view was overshadowed by at least ~5 experts who said the opposite, along with basically all blog posts on the subject. In summer 2008, I decided the weight of evidence was overwhelming and instead set out to apply directly to software companies for a job after graduation.

This proved undoubtedly to be the right decision. Within 3 years at Microsoft, I was promoted (at a normal promotion speed) to the same level at which PhD hires typically started. So by working in a company, I essentially got a fast-tracked PhD-equivalent. Plus, I avoided 5-6 years of lost income that I would have incurred had I gotten a PhD. A few years after I started working, a friend who did get a PhD began applying for jobs very similar to mine. He said: "Brian had the right idea in not getting a PhD."

A similar trend applies for most careers. Most startup founders don't have a PhD, so even if you're shooting for a startup, you should probably just do that directly. PhDs are not important on Wall Street except for elite quant jobs or perhaps certain kinds of stock analysis, nor are they helpful in most other business jobs.

A PhD may make sense if your goal is not earning—e.g., if you're studying applied ethics. Ask a lot of people for advice before beginning a PhD program, and read about what to expect. Getting What You Came For is a helpful book with testimonials from many grad students.

Keep in mind that PhDs take a long time, and you're decently likely to change your mind about what you should be doing in the intervening period. Then you'll either have to continue a suboptimal degree or leave without the PhD. Many people advise that if you do get a PhD, you should wait until you've worked for a few years. I think this is excellent advice for any advanced degree. A PhD is like marriage. It's generally best not to get married until at least your late 20s. When you're young, you might fall in love with a topic and think you want to get married to it, only to break up with it a few months or a few years later.

I don't think it should be that hard to get into a PhD program after working for several years, because you can begin by doing research assistance and publishing papers before applying to programs.

If you do drop out of a PhD program, you can often at least leave with a Master's degree if you took the required courses and exams. While getting a Master's degree in this way is nominally "free" compared with paying $40K/year for a terminal Master's, tuition is replaced by teaching-assistance work for PhD students (say, 20 hours/week), which may (or may not) pay less per hour than the job you'll get upon graduation. In any case, admission to PhD programs is more selective than to Master's programs, and it seems dishonest to enroll in a PhD program purely with the intent of dropping out early.

Interview prep

For many jobs, the interview constitutes a large part of the decision to hire you and what salary you'll be offered. For technical interviews, there's no such thing as studying too much. It's recommended to take at least several weeks to prepare if you can.

For quant jobs, Heard on the Street is a standard reference. Among other things, it contains a number of fun puzzle questions.

For software, two standard books are

I recommend reading both as thoroughly as you can. You'll also find tons of advice on the web, including blogs where people describe their experiences interviewing at a given company. Since software interviews focus on algorithms and big-O problems, it's ideal if you can take your college's most advanced Algorithms course near in time to the interview, because then the material will be fresh in your head. (I gave up an economics minor in order to rearrange my schedule to do this during college. I don't regret the decision.)

Consulting often uses case interviews, especially involving Fermi problems. I haven't studied these in as much depth, but you should probably get a book or two about them.

Some people recommend practicing interviews "live" with a friend, especially for whiteboard coding. I never did this myself and didn't find it very necessary, but YMMV.

When scheduling interviews, some suggest putting the easier or less desirable companies first so that you can practice on them.

Negotiating offers

It's best to apply for jobs all at once so that you can interview all around the same time. Your goal is to get as many offers as you can at once so that you can play them off each other to improve your salary. This is especially true if you most want to work at a company whose offer isn't the most lucrative. You can tell your recruiter at the desirable company about the other, higher offer and probably get a boost to the offer from the desirable company. You can read up on advice for what kind of language to use in these communications.

Your offer matters not just because of the remuneration you'll get the year you start working but because your remuneration now affects your remuneration all the way into the future. Generally your pay doesn't decline over time (unless you change industry), so an extra $5K offer might mean an extra $100K over the next 20 years (ignoring the time value of money).a

One other factor to consider in assessing an offer is how big the company's matching-donations program is. Since most employees don't max out the matching limit, matching donations are a special bonus for altruists. That a company has a high matching limit doesn't mean its regular compensation offer will be lower.

Ceteris paribus, states with lower tax rates or housing costs may be good. I've heard that sometimes pay is equal within a company across states, which presents a bonus for those in the cheaper states. I think in other cases jobs pay more where cost of living is higher. States with low income and high sales tax benefit those who are frugal. All of this said, job compensation takes precedence over cost of living, so don't shy from moving to Manhattan or San Francisco just because of living costs.

During your job

Figure out how performance is assessed in your company. There may even be training courses about this sort of thing. What's expected of you in order to be promoted? Who has input to the decision? Human Resources may have general, vague guidelines about these sorts of things, but within your specific division, the picture of what managers want is likely much more concrete.

Your company may have a semi-annual or annual review process in which you describe what you accomplished and get peer feedback. I used to keep a running list of my accomplishments, as well as of coworkers from whom to request recommendations, so that I wouldn't forget key points.

Management attitudes towards employees often revolve around high-level labels and stories. "He's the guy who did X." "She did a good job with projects Y and Z." Being able to "own" a project and having a clean, simple way to pitch your accomplishments can be helpful. Of course, you also need to do the messy, detailed work behind the scenes and be able to answer questions about it when asked.b

Also use your time at your job to network with other employees, especially if they might have similar interest in your altruistic causes. Your place of employment is home to many wealthy people, though the fraction of them who intend to donate a lot of money is probably quite low.

Interviewing with other companies

People who stay at one company tend to earn less than those who move around. This is because those who move need higher offers to be enticed away from their current jobs, while those who tend to stick around don't need to be given as many promotions and raises.

If you don't actually want to move, you can still (silently) interview with other companies to see if you can get a higher offer and then take this offer back to your current employer. You can say, "I really want to stay here, but I might be forced to leave for a better opportunity unless I can earn more in my present position." Doing this can be unnerving to your bosses, so I think it's not advised to bargain for a raise like this too often. Also, if you keep declining the offers from other companies where you interview, they may stop liking you. Don't interview with an excellent possible employer only to turn them down, because this may burn bridges for when you really do want to take their offer.

While sticking with one company forever is probably not optimal for earnings, neither is switching too often, because this might make you seem unloyal to possible future employers.

Acknowledgments

Much of what's written here I learned from teachers, professors, fellow students, alumni, coworkers, friends, and—most of all—books, blogs, and forums. The JavaScript calculations in the Appendix were partly inspired by Peter Hurford's "Vegetarian Impact Calculator". Ben West gave me insights into startup expected-value estimation.

See also

Appendix: Comparing software industry vs. quant hedge funds

Introduction

This appendix compares earnings as a programmer in the software industry (Google, Microsoft, etc.) against those as a quant programmer at hedge funds. Because it focuses on long-term payoff, it assumes the hypothetical employee has 10-15 years of experience.

The tax calculations are roughly based on 2014 or 2015 rates and assume you're filing as Single. The tax calculations are only approximate, because it would have been complicated to make them more precise.

In the following table, I've tried to assume a constant level of ability for the hypothetical employee among the different options, but I probably haven't done this perfectly, so feel free to revise the numbers. According to this post, "The very top hedge funds are harder to get into than the very top software companies, simply due to the size of the workforce." That's why I haven't used the uppermost estimates of hedge-fund compensation that people give online in the table below; I assume it's pretty hard to break ~$500K in average annual hedge-fund earnings, harder than becoming a Senior or Principal engineer at Google or Microsoft.

Input assumptions

Results

| Software industry (WA) | Software industry (San Fran) | Quant developer at hedge fund | Programmer at Soros Fund Management | |

| Donatable $/hour (after taxes and costs of living) | ||||

| Total donatable income | ||||

| Federal income tax | ||||

| State income tax | ||||

| Local income tax |

Note that the differences among these options may be slightly smaller than they appear if there's diminishing marginal value for additional donated dollars.

Other considerations for Silicon Valley vs. Wall Street

Other advantages for hedge funds:

- Colleagues will be wealthier.

- It's not obvious whether speeding up tech is good or bad, so even though conventional wisdom attributes more social value to Silicon Valley than Wall Street, the actual assessment is unclear.

- Use of math is more advanced in quant finance than most of tech, even machine-learning tech. (I forgot the source from which I read this, but it jives with my experience.)

Other advantages for tech industry:

- Conventional wisdom suggests that tech benefits society in a positive-sum way by creating wealth, while hedge funds just transfer wealth in a zero-sum way.

- Friends and relatives who haven't analyzed the situation in depth will probably look more fondly on your working in Silicon Valley rather than Wall Street.

- Shorter hours and less stress mean lower chance of burnout and longer life expectancy.

- Less greedy atmosphere and lower chance of losing altruistic ideals.

- Quant trading may become less profitable in the future due to regulation or competition (source), while tech seems unlikely to slow down in the long run.

- Tech is more laid back: flexible hours, no suits, sometimes working from home. (That said, some quant hedge funds can have relaxed dress/work environments too.)

- Possibly more potential to create startups and network with billionaires (especially in Silicon Valley rather than Seattle).

- A few tech companies like Microsoft have individual offices, which means less distraction by noise. Individual offices also make possible using treadmill desks. Probably few hedge funds allow treadmill desks.

Sources for the default values in the table

Software industry (WA)

Compensation

According to Glassdoor, a Senior Software Development Engineer (SDE) at Microsoft in the headquarters area with 10+ years of experience earns $175K/year in salary + bonus. The same figure for a Principal SDE is $240K.

Donation match

Microsoft's match is $15K/year. Amazon doesn't have a matching program.

Costs of living

The default numbers in the table are based on my experience living in the Seattle area. They also jive with what I see browsing Seattle Craigslist apartments.

Software industry (San Fran)

Compensation

According to Glassdoor, a Senior Software Engineer at Google in the headquarters area with 10+ years of experience earns $254K in salary + bonus.

"I know a couple of developers [in Silicon Valley] (well, technically they're developers/pseudo-managers) in their late 20's/early 30's making in the $300,000-ish range, but compensation isn't likely to grow significantly past that particular juncture. It's hard to add significantly more value than that unless you get involved in the more 'Product Management' type roles." (source)

Donation match

Google's match is $12K/year.

Costs of living

According to CNNMoney, compared to Seattle, WA, in San Francisco, groceries cost 11% more and housing costs 83% more. See also apartments on San Francisco Craigslist.

Quant developer at hedge fund

Compensation

- A recruiter told me in 2011 that quant developers can make about double those in Silicon Valley. Another recruiter told me in 2015 that I could earn up to $300K-500K per year doing quant programming within a few years.

- "Fresh out of school, you’ll probably get more in Silicon Valley than Wall Street, where base salaries start low. But after 3-4 years on Wall Street, you can be pulling down $500,000 with bonus. In 5-7 years, that’s $1 million. No doubt about it, on Wall Street, you’re definitely going to make a lot of money." (source)

- "Most of the time I’m speaking with 'elite' stats/cs/machine learning gurus who have offers from Teza, Citadel, Two Sigma and/or Rentech as well as Google, Facebook and 2-3 top start-ups. The hedge fund quant jobs are $400-$600k with total comp of up to $1mm, and the others are, well, substantially less." (source)

- "After perks, bonuses, etc, you will probably make about the same at a hedge fund as at Google/Facebook. You might make a little more at the hedge fund (e.g. 250k vs 200k). The best quants can get into the 400k-1m/year range, and that is pretty hard to do at Google or FB (although possible if you're truly elite)." (source) But a comment on that answer says: "I would say the numbers on hedge fund comp, at least at a decent size fund, are understating the trajectory curve. May be the case when first starting out, but a few years in and the disparity grows pretty quickly."

- "In the US, a position like that would have a floor of somewhere around $100-120k, and would be making $150-250k within five years." (source)

- "High frequency trading (HFT) firms [...] pay up to $150k in your first year and close to $290k after two years." (source) The same article lists average compensation for several firms. I'd put the median estimate around ~$400K-$500K, with some estimates lower and some much higher.

- "The pay is better at hedge funds, but *on the average*, it's better by only about 30-50% versus a comparable job in technology." (source)

- Hedge funds "are looking for someone who is one of the ten best in the world in Machine Learning. They aren't passing any ol' ComSci PhD over half a million a year. There are only a few firms who are all trying to woo a few different people." (source)

- "It is common to see salaries of ~$250,000 and bonuses of $500,000 for experienced quants. The compensation also partly depends on the profits of the firm. An entry-level position in quants can earn you a starting salary of $125,000 to $150,000." (source)

Hours

- The author of "A Day in the Life of a Quantitative Developer" reports at least 12 hours of work in his typical day. Over 5 weekdays that's 60, and add some on weekends as well.

- "I code at an IB in London. I have several friends who have recently started work at hedge funds. The work sounds interesting but the pressure can be high. I work a 'reasonable' 50ish hr week - they all work longer (sometimes much longer)." (source)

- "At my firm, we were expected to work for 45 hours, 5 days, but in actual terms, it approached 50-55 hours on average. Some crazy weeks made it go to 70 hours too." (source)

- "If you want to keep your job, at least 50 hours/week. If you're engrossed in a project, it can approach 60, but usually by choice, not by force or expectation." (source)

- "40 hours by contract, 50 in practice. The extra hours are due to production problems most of the time." (source)

Costs of living

According to CNNMoney, compared to Seattle, WA, in Manhattan, groceries cost 21% more and housing costs 165% more. Apartment prices on Manhattan Craigslist seem about the same as the default value my the table. This page suggests average studio prices of ~$2500 for non-doorman apartments, which is slightly lower than what's in the table above, but this is counterbalanced by the fact that CNNMoney suggested ~$3700 based on comparison with Seattle. I split the difference and chose $3000.

Programmer at Soros Fund Management

Compensation

According to Glassdoor, here are some base salaries for a few positions:

- Systems Engineer: $139K

- Network Engineer: $96K-103K

- Quantitative Analyst: $170K-184K

- Quantitative Developer: $127K-139K.

Bonuses aren't specified, but they'd probably make the total come to at least ~$150K on average.

Donation match

See "Donate $400K per Year by Working at Soros Fund Management".

Footnotes

- I learned this point from an article that I can't now find. (back)

- People who aren't knee-deep in a topic tend to respond best to stories. We can see this not just when talking to management in a business but also in realms like news/magazine articles, donor solicitations, and so on. Outsiders may be more interested in the general problem that you're working on than in whatever specific contributions you made yourself. Sometimes a researcher sells his work to the media simply by telling a good story about the high-level insights of his field. Of course, this doesn't work well if the person you're talking to knows a lot of details already. (back)