by Brian Tomasik

First published: 7 Feb. 2017; last update: 7 Feb. 2017

Summary

It's sometimes claimed that entomophagy (eating insects) requires less crop cultivation than eating plants directly. While this can occasionally be true in principle, the claim is usually false in practice. In most commercial farms that produce human-edible insects, the insects are fed grains, fruits, and vegetables that could be eaten by humans directly.

Contents

Epigraph

When insects are hailed as an environmental savior, it is often assumed that they will be raised on food waste and similar resources. But so far, most large-scale commercial insect farming involve[s] feeding the insects farmed grains, which makes the insect farming similar to raising livestocks such as grain-fed chicken and grain-fed cattle.

Introduction

Fischer (2016)'s article "Bugging the Strict Vegan" contends that some vegans may find entomophagy preferable to eating plant-based foods because mechanized crop cultivation kills clearly sentient animals like mice and birds on crop fields. Of course, farmed insects also need to eat, and given that food energy is lost moving up a trophic level, more calories of plants often need to be eaten by bugs to provide a given amount of nutrition to a human than if the human ate the plant food directly. This point completely reverses Fischer's argument, but Fischer devotes only a single paragraph to this central objection (p. 7):

The strict vegan might object that we’ll end up feeding plants to insects, which will entail harming one set of insects to raise others. This would probably skew the numbers back in favor of eating a strict vegan diet. However, we needn’t feed insects new plants. One of the wonderful things about insects is that, as natural recyclers, they can live primarily on food waste. We might increase the efficiency of the food system by giving these creatures a more prominent place in it.

While it's true in principle that human-edible insects could possibly be fed "organic side streams" such as food waste, this is not how most human-edible insect food products in developed countries are actually produced. Most such insects are fed high-quality grains, fruits, and vegetables. Promoting entomophagy on the basis of a theoretical possibility when actual practice is largely different is like encouraging people to eat McDonald's chicken nuggets based on a few anecdotes about a rare chicken farm where the birds are very happy and are killed painlessly. (Note: In practice, I think most small-farm animal slaughter is very far from humane. Also, on free-range chicken farms, chickens may cause pain to lots of bugs in the grass by eating them.)

Maybe Fischer intended his argument as purely hypothetical, speaking to a possible future world in which human-edible insects are largely farmed on organic wastes. If so, it would be important to clearly state this in order to prevent well meaning people from eating more insects produced via current methods. (I personally oppose insect farming on organic wastes too, but this is a separate argument, which I discuss more in another article.) Fischer relays (p. 8) that "I know one strict vegan who has taken these arguments to heart. He has since become 'veganish'—a term he coined to describe someone who supplements an otherwise plant-based diet with crickets, mealworms, and the like." Unless this veganish person is sourcing his insects from very particular sources, he's likely causing net harm even according to the goal of reducing crop cultivation.

Insect feed on farms

Let's examine what farmed insects actually eat. In Dec. 2016, I searched for articles and videos explaining the process of growing insects at various developed-world insect suppliers. Below is a list of the sources I found that discussed what the insects were fed. Readers are welcome to send me additional information to add here.

| Farm | Feed |

| Big Cricket Farms (Youngstown, OH, USA) | "currently feeds the crickets with organic chicken feed, but plans to eventually use food waste from around Youngstown." (source)

"Filtered water and an organic grain-based diet, supplemented with occasional cabbage and parsley, round out the amenities. [...] Bachhuber began discussing the possibilities of improved cricket feed. Small-scale studies have shown that by replacing grain with skim milk and brewer’s yeast [one] can create cricket Arnold Schwarzeneggers, while feeding the crickets carrots for several days before harvest gives them a faint carrot flavor." (source) The crickets "enjoy organic OMRI feed. In the final days of their life, Bachhuber will give them fresh, organic vegetables to fatten them up (and, he admitted, to assuage his guilt)." (source) This video shows the farm using bags of Natures Grown Organics chicken feed. Given that the crickets are currently given chicken feed, it's not clear Big Cricket Farms is any more food-efficient than poultry production (as I discuss later), and it's less efficient than eating the input grain/etc. directly. If the farm were to switch to food wastes, that would be a different story, but (1) this hypothetical doesn't apply to current consumption of these crickets and (2) I'm not sure that switching to food wastes will actually work (as I discuss later). (Actually, as of late 2016, I think Big Cricket Farms has now closed, with some of the team having moved to Bugs, Inc.) |

| Aspire Food Group | "A local mill mixes the crickets’ organic grain-based feed. Farms sometimes add other ingredients to bolster their feed, like flax seeds and essential fats to increase the level of omega 3s." (source) |

| Kreca | This video shows mealworms being fed. It's not stated what the feed is, but it looks to me like grain? A Kreca representative says at 2:22: "Most of the insects are for the animal consumption, but we have one insect also for the human consumption." |

| Entomo Farms (formerly Next Millennium Farms) | This video shows insects being fed. It's not stated what the feed is, but it looks to me like grain? |

| Tiny Farms (Berkeley, CA, USA) | "It uses a process called gut loading – in which crickets are fed certain flavoured or nutrient-rich foods just before they are killed – to rear crickets that taste like honey and apples, or that are high in vitamin C." (source)

According to Andrew Brentano of Tiny Farms: "Our silkworms were raised in an environmentally controlled tent and fed a prepared feed made with powdered mulberry leaves. The mealworms can be raised at room temperature (ideally close to 70 degrees F) in shallow plastic or metal trays in a bedding of wheat bran or other grain byproduct, and should be fed additional vegetables like carrots for moisture." (source) I don't know if the mulberry leaves are from wild or farmed plants. This page says: "mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions.[2]" This page says: "Mulberry is cultivated for fruit as isolated trees or in orchards; for small scale silk worm rearing along the edges or along food crops in mixed farming systems; for large silk projects or for intensive forage production in pure stands; and also for forage in association with N-fixing legumes (Talamucci and Pardini, 1993; González and Mejía, 1994). Mulberry is also found mixed with other trees in natural forests or plantations." |

Lundy and Parrella (2015) confirm the point revealed in the above table: "as with most livestock production, commercial cricket production relies on grain products as a feed source."

Wikipedia's article on "Insect farming" says regarding house crickets:

Until they are twenty days old they are fed high protein animal feed, most commonly chicken feed, that contains either 14% or 20% of protein. Once they finally reach twenty days old they can be fed a mixture of the two. A few days before harvesting the crickets at forty-five days old the crickets are fed various vegetables such as pumpkins, cassava leaves, morning glory leaves, and more. This is done to improve the taste of the insects and reduce the use of the expensive, high protein animal feed.

Note that humans can eat cassava leaves directly (and, of course, pumpkins too).

Feed for home-grown insects

I also searched for information on what people feed insects that they grow in their own homes for consumption. Below is a comprehensive list of what I found, and once again, I welcome additional data points.

| Feed | My comments |

| "Feed [the baby crickets] high-protein foods like tofu and chicken, and they’ll grow quickly." (source) | So much for not wasting high-quality food! |

| This video shows small-scale farming of mealworms. They're fed mainly oats, along with some carrots. | |

| This video shows farming of black soldier flies. The feed contains apples amidst some other substrate (wood shavings? grain? I can't tell). | |

| This video shows mealworms being fed wheat bran (1m44s into the video), as well as some carrots and celery (3m10s into the video). | These mealworms are grown for geckos, not humans (4m03s into the video). |

| "Feed the adults plants like cucumber, morning glory, and pumpkin. What you feed them can affect how they taste, so feel free to experiment. Robert Nathan Allen of Little Herds, an Austin-based nonprofit dedicated to inspiring more insect-eating, explains: 'Feed them mint, and they’ll taste minty; feed them apple and cinnamon, and they’ll taste like apple and cinnamon.'" (source) | Except for morning glory, the foods mentioned here are cultivated crops. Also, if you have to deliberately plant morning glories, you should be planting edible crops instead, to minimize total plant farming, assuming you're as worried about the impact of plant farming as the entomophagy advocates claim to be. Feeding insects on wild-growing plants would be an exception to my general point in this piece. That said, many wild plants are also human-edible.a |

| "The methods used in cricket farming in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Thailand and Viet Nam – veteran producers of crickets – are very similar. In these countries, crickets are reared simply in sheds in one’s backyard, and there is no need for expensive materials. [...] In each 'arena', a layer of rice hull (or rice waste) is placed on the bottom. Chicken feed or other pet food, vegetable scraps from pumpkins and morning glory flowers, rice and grass are used for nourishment." (van Huis et al. (2013), p. 102) | It sounds like some of these cricket-feed substances might be human-edible, while others are not. I would guess that most or all of these feedstuffs could be eaten by other livestock, such as chickens. (For example, chickens can eat grass.) |

What about using food waste?

Lundy and Parrella (2015)

Lundy and Parrella (2015) examined the possibility of feeding "organic side-streams" to house crickets (Acheta domesticus) "at a much greater population scale and density than any previously reported in the scientific literature." The authors note that several past studies had reared insects on organic wastes, but

the contexts in which these results were measured do not generally reflect the scale or the degree of control likely to resemble an economically viable production process. In addition, population densities in these studies were generally low, suggesting that, while the conversion efficiencies reported may be accurate on an individual basis, they may or may not apply to production environments with high-density insect populations.

Lundy and Parrella (2015) raised crickets for themselves. The authors found that the crickets grew well on "a 5:1 ratio of non-medicated poultry starter feed and rice bran" (the so-called "PF" treatment), as well as on "the solid, pasteurized, post-process filtrate from a proprietary, aerobic enzymatic digestion process [29] that converts grocery store food waste into 90% liquid fertilizer and 10% solids (the portion used in the experiment)" (the so-called "FW1" treatment). However, there was over 99% mortality for the other three treatments tried, one of which was "minimally-processed, post-consumer food waste collected from municipalities throughout California’s Bay Area."

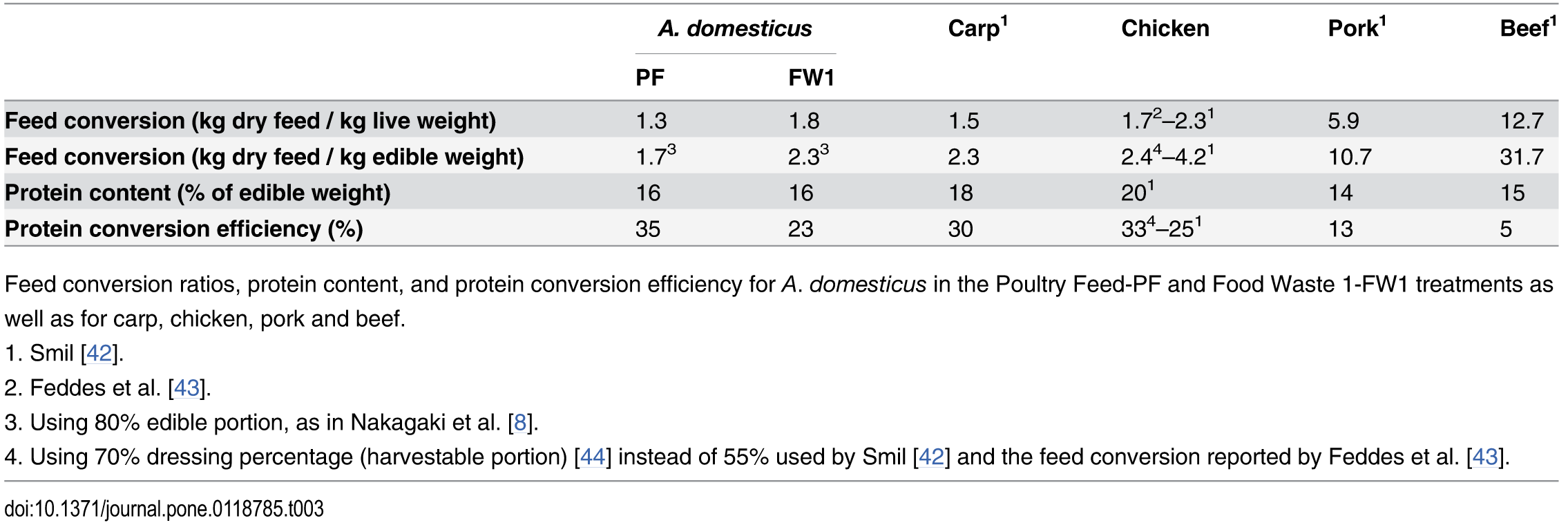

Even on the feeds that were conducive to cricket growth, feed-conversion efficiencies weren't necessarily better than those for carp or chicken (Table 3):

The authors explain: "Even if global demand for crickets were to exist at a much greater scale than it does at present, a novel protein source with little or no [protein conversion efficiency] PCE improvement compared to chicken is unlikely to justify the investments required to produce crickets at a scale of global significance."

Other numbers on insect feed-conversion efficiencies:

- Collavo et al. (2005) found (p. 533, Table 27.7) an ECI for Acheta domesticus crickets of 59%, compared with chicken ECIs from the literature of 35% (based on a 1963 study) and 48% (based on a 1979 study). However, I would guess that present-day chicken ECIs are quite a bit better than what these old studies found, given that, according to Steinfeld and Gerber (2010), "Measured in global protein output per standing livestock biomass, [...] over the past two decades[...] productivity of monogastrics (pig and poultry) grew at an annual rate of 2.3% (8)."b

- Kevin Bachhuber provides some real-world numbers on crickets: "On average, for 40 pounds of crickets, we'll use between 70 and 80 pounds of feed. It's basically a 2-to-1 utilization ratio. There's a lot of room for improvement, even on that number. We're learning more about cricket nutrition. We can probably get it down to 1.5 or so. When I talk to old cricket farmers in the U.S., it was 2.5 pounds per 1 pound 20 years ago."

- For comparison, Best (2011) reports: "a laying hen may eat 11 kg of feed in producing 5 kg of eggs. This would indicate her [feed-conversion ratio] FCR as being 2.2:1. Assuming the edible contents of a 60-gram egg weighs 55 grams, the feed conversion for this production becomes 2.4:1. The extent of cooking losses may be 2%, so the FCR for the edible content would become 2.45:1." Best (2011) also reports: "Since the early 1960s, broiler growth rates have doubled and their FCRs have halved."

A news piece about the Lundy and Parrella (2015) study quotes the study authors:

“Everyone assumes that crickets — and other insects — are the food of the future given their high feed conversion relative to livestock,” Dr. Parrella said. “However, there is very little data to support this, and this article shows the story is far more complex.”

“I’m all for exploring alternatives, and I am impressed by the amount of innovation that has sprung up around insect cultivation and cuisine in the last few years,” Dr. Lundy said. “However, while there is potential for insect cultivation to augment the global supply of dietary protein, some of the sustainability claims on this topic have been overstated.”

Regular farm animals can also eat food waste

Lundy and Parrella (2015) explain:

As noted by Elferink et al. [47], scalable organic side-streams are already being used in the production of pork, and a scalable substrate that is high in protein content might share demand with swine and other forms of livestock. Therefore, identifying regionally scalable waste substrates of sufficient quality to produce crickets that have no direct competition from existing protein production systems might be the most promising path for producing crickets economically, with minimal ecological impact, and at a scale of relevance to the global protein supply.

In other words, Fischer's praise for animal products that consume organic wastes can also apply to some ordinary livestock, although the praise may be somewhat muted by lower conversion efficiencies.

Elferink et al. (2008), the study cited by Lundy and Parrella (2015), reports (pp. 1227-28):

Livestock is[...] not only fed crops. In industrialized countries livestock is fed with concentrates purchased from the feed industry. To produce concentrates the feed industry purchases feedstock from international markets. [...] The feedstock purchased includes not only crops (wheat, maize, soybeans, tapioca, etc.) but also food residue from, for instance, the food processing industry (oilseed scrap, molasses, potato peels, etc.). Currently, 70% of the feedstock used in the Dutch feed industry originates from the food processing industry [16]. These food residues are generated due to consumption of vegetable or vegetable-based foodstuffs. [...] Feeding food residue to livestock can be seen as an effective option for handling waste, because it transforms an inedible stream into high quality food products, such as meat, milk, and eggs.

In addition (p. 1232):

When food residue is no longer available feed grains are required. At current animal food consumption levels all food residues generated per person are already used for feed purposes. This means that a further increase in animal food consumption requires grain-based feed.

This page explains:

The primary waste products fed to swine are plate and kitchen waste, bakery waste, and food products from grocery stores. The primary sources of plate waste are restaurants, institutions, schools, and, to a small degree, households. [...]

Feeding food waste to swine has been common in the United States, especially in rural areas adjacent to major metropolitan areas. This practice has declined in recent years because of stricter federal, state, and local laws regulating animal health, transportation, and the feed usage of food waste. Although the feeding of raw (unprocessed) food waste to animals has been limited, there are still many states that allow it in some form.

It was mentioned previously that Tiny Farms fed mulberry leaves to silkworms. But other livestock can also eat mulberry leaves: "The leaves can be used as supplements replacing concentrates for dairy cattle, as the main feed for goats, sheep and rabbits, and as [a]n ingredient in monogastric diets." For example: "In rabbits, the reduction of concentrate offered daily from 110g to 17.5g with ad libitum fresh mulberry only reduced gains from 24 to 18g/d, but decreased to more than half the cost of the meat produced (Lara y Lara et al., 1998)."

Safety of food wastes

Concern about the quality of food waste, as mentioned above in the case of pig feed, may also apply in the case of insect feed. For instance, this article quotes Kevin Bachhuber, founder of Big Cricket Farms, as saying that some insects bred for pet food are raised on "gone-off dog food, and that’s obviously not OK for human consumption".

van Huis et al. (2013), the famous FAO report on entomophagy, includes a discussion of "organic side streams" (pp. 61, 66):

Other insect species, such as crickets, are raised on insect farms and fed with high-quality feed such as chicken feed. The substitution of such feed with organic side streams can help to make insect farming more profitable (Offenberg, 2011). However, at present this is not permitted because of food and feed legislation [...].

The possibility of rearing insects on organic waste for human consumption is still being explored, given the unknown risks of pathogens and contaminants [...].

insects are potential vectors of medically relevant pathogens, including the eggs of gastrointestinal helminths found in human faeces. The risk of zoonotic infections (transmitting diseases from humans to animals and back) could rise with the careless use of waste products, the unhygienic handling of insects, and direct contact between farmed insects and insects outside the farm due to weak biosecurity.

This page reports: "Dr. Adrian Charlton, a biochemist at the UK’s Food and Environment Research Agency, says that crickets raised on food scraps and manure could suffer from fungus, bacteria, drug, or metal contamination—and we wouldn’t know until we ate them and got sick ourselves."

Will entomophagy companies eventually use food waste?

In response to a comment of mine about the topic in this piece, Taponen (2015) wrote:

To my knowledge at the moment there are no companies doing this [i.e., using food wastes] in industrial level. However, it is fair to notice that there are only a few industrial-size companies doing any kind of insect products for human consumption. I am sure that when the insect- products became more common and more companies join in producing them we will see insect products for human consumption fed on waste.

I'm not an expert on the cost structures of insect production, but it's plausible to me that entomophagy companies will continue using a grain-heavy diet for most human-edible insects because

- Grain is cheap, in part due to agricultural subsidies.

- Grain leads to faster growth (see Lundy and Parrella (2015), Fig. 1). Keep in mind that beef cattle could also be raised entirely without grain, but they usually aren't, in part because "Grain-finishing is more efficient and takes less time than grass-finishing."

- The entomophagy industry can't afford the PR disaster that might result from using more questionable feeds.

Taponen (2015) himself mentioned some other challenges with using food wastes:

the non-consistent composition of waste compared to high-quality feed that is made for the insect. This can cause problems in the storing and the daily farming routines. Some insects eat naturally manure and urine. Using these two externalities of livestock farms would be very beneficial economically, but there is a danger of accumulation of heavy metals.

Insects as animal feed

My impression is that most insects reared on organic wastes are used as animal feed rather than human food. But providing feed for livestock isn't exactly a great victory for the veg*ans whom Fischer was trying to win over to entomophagy.

Enterra Feed Corporation in Langley, British Columbia, Canada produces black soldier fly larvae using raw pre-consumer food waste. However, the larvae seem to be fed to non-humans: "feed for fish, poultry, pets and zoo animals."

This article says: "a factory being built by Agriprotein in Cape Town, South Africa, will turn food waste into animal feed by raising flies en masse." Although "people can eat" the insects as well, "it’s not the main purpose" of the farm.

Taponen (2015) says:

There [are] at least two companies that have announced that they use waste as feed for the farming of the black soldier fly. The fly is not fed to humans, but to for example fish farms that produce products for human consumption. A certain insect company says they are using offal-waste, second example company says they are using “pre-customer” food waste. When the companies are using these types of wastes that are consistent by quality and the one eating the final product is not a human, the two challenges [with using food wastes] mentioned earlier are not issues.

van Huis et al. (2013), p. 105:

In choosing a feedstock it is important to know whether the insects are destined for feed or food. For insects to be used as feed, different (organic waste) side streams need to be evaluated. Insects intended for human consumption need to be fed feed grade or even food grade food if the insects are not to be degutted. Waste streams might not be a viable option for human consumption; this area demands further research.

Using waste still slightly increases crop cultivation

The following point is not very important and is included mainly for the sake of completeness. While buying plant foods directly increases crop cultivation, buying food wastes to feed them to insects or other farm animals can be expected to slightly increase crop cultivation as well, because food processors earn a bit of income from selling food scraps, which encourages them to process (and therefore purchase) slightly more food than before.

Elferink et al. (2008), p. 1228:

food residues have become useful products and the food industry derives nowadays a profitable income from selling their food residues. Furthermore, food residues can be used for multiple purposes. Besides as a feed ingredient food residues can, for instance, also be used for providing renewable energy. Due to the economical value and the multiple uses of food residues Zhu and van Ierland [23] argue that food residues should be ascribed an environmental impact.

As one example, Elferink et al. (2008) report (p. 1230, Table 2) that for a given quantity of sugar beets, 91% of the sale-price value comes from sugar (the main output product for human consumers), with 5% of the value coming from left-over beet pulp and 4% from left-over molasses. Meanwhile, only 59% of the mass of sugar beets goes into sugar, while 24% goes into beet pulp and 17% goes into molasses. The byproducts have less value per kg than sugar does, so consumption of 1 kg of byproducts probably contributes less to sugar-beet production than consumption of 1 kg of sugar does.

Feeding insects your own food scraps

So far we've seen that most insects sold to end consumers are produced with human-edible input feed, not food waste. "But," some might say, "I could at least grow my own insects with food waste." Fortunately for the insects, most people won't actually go to the trouble of doing this. Even if your goal is to reduce crop cultivation, probably there are more effective ways to do that than by painstakingly tending to and sorting through a small home insect bin. Even if you are tempted to kill large numbers of sentient creatures in your house, I would suggest to think about whether you can reduce the amount of food waste you produce instead.

Personally, I generate two main types of food waste:

- Parts of foods that aren't good to eat, such as orange and banana peels, apple seeds, grape stems, etc.

- Edible food that happens to go bad, usually due to not being eaten soon enough.

I produce very little of the second kind of food waste, because I keep track of the foods in my fridge and make sure to finish them on time. My housemate is much more careless about such things, but I also usually succeed in eating my housemate's aging food before it's too late. This isn't very difficult and is probably much easier than farming, freezing, and cooking your own insects.

And as far as the first kind of waste: Many forms of "food waste" are actually edible, including orange peels and banana peels, although the human digestive system may not absorb all the nutrients in these peels: "Nutrition experts say that while there are many interesting nutrients in the banana peel, the amounts are small and, more importantly, there aren’t any studies showing that our bodies can actually absorb them." The main reason not to eat skins is if they're covered in pesticides. But if they're covered in pesticides, it's not clear that you want to feed them to insects either:

- This page says: "Herbicides can accumulate in insects through bioaccumulation."

- van Huis et al. (2013), p. 105: "the feedstock needs to be [...] above all free of pesticides and antibiotics."

- This page warns: "Make sure there are no pesticides in what you give your crickets (the chemicals would kill them)".

What if you already compost?

While I suspect that entomophagy increases invertebrate suffering in practically all cases, it's at least less bad when it harvests invertebrates from existing invertebrate-dense composting operations, such as vermicomposting bins. Decomposer bugs in compost bins would die anyway, and killing them to eat only hastens death. (Hopefully these bugs would be killed by freezing rather than by more inhumane methods like heating. This page gives cruel advice about how to kill earthworms for human consumption: "The worms are blanched in 60 degrees Celsius water to kill them.") Still, killing animals prematurely may increase the number of deaths per unit time and thus total suffering.

In any case, I also oppose invertebrate-dense composting for the same reason as entomophagy: It creates large numbers of invertebrates who will die, perhaps painfully, not long after being born. So composting is not a good excuse for eating bugs, in my opinion.

Instead of composting, I recommend not generating food scraps or disposing of food scraps in sealed garbage bags or via a sink garbage disposal unit. An upcoming piece on this site will discuss this topic in more detail.

If you think eating vermicompost worms is great because it (slightly) reduces your need to buy mechanically harvested crops, you should presumably also support raising your own chickens and feeding them food scraps. Of course, I don't support either option, because significant suffering is caused by slaughtering the animals you raise. But my point is that insects are not somehow uniquely special in their waste-recycling abilities.

This page says regarding feeding chickens food scraps:

In the UK back before these regulations and still in many countries, the scraps pan was a fixture in the poultry keeper’s kitchen. Into the pan went most anything that would go into a compost bin. Potato peelings, carrot tops, cabbage and cauliflower stalks, the scrapings off the plate and small bones, stale bread and cake. [...]

Fresh greens direct from the garden can still be fed even in the UK. These provide vitamins and interest to the birds. Bolted lettuce, the outer leaves from cauliflowers, tomatoes that some pest has nibbled all go down well.

Mushroom farming

Animals are not the only macroscopic heterotrophs that can be fed organic wastes. Mushrooms are already farmed at a relatively large scale on organic wastes.

Mushroom Farmers of Pennsylvania (n.d.) explains:

At the farm, the grower carefully prepares the basic growing medium for mushroom production, which is called substrate – a key ingredient in mushroom production. Two types of starting material are generally used for mushroom substrate: synthetic compost consisting of wheat or rye straw, hay, crushed corn cobs, cottonseed meal, cocoa shells and gypsum, or manure-based compost made from stable bedding from horse stables or poultry litter.

To maintain compost structure for aeration during composting requires a base of organic fibrous material to keep the piles loose and provide carbohydrates for the nutrition of the mushroom. One Pennsylvania farm has worked with their local municipality to use the leaves collected in the township during the fall. They have successfully used the leaves in their composting process and now are considering improved ways to store and handle[...] larger quantities. Paper waste will add cellulose to the compost, but only added at a low amount per ton of dry material. More research into this area may be valuable to find a use for the tremendous amount of junk mail and paper waste.

[...] municipal governments and communities should look to mushroom farms as a disposal agent. Researchers should be more interested in testing and using agricultural and industrial waste products for mushroom compost.

Barney (n.d.), pp. 4 and 6:

Substrates (materials the mushrooms grow in) are blended and packaged into special plastic bags or jars. Typical substrates include sawdust, grain, straw, corn cobs, bagasse, chaff, and other agricultural byproducts. [...]

Researchers have developed methods of effectively and economically producing many species of edible mushrooms. These production systems use agricultural waste products, including straw, chaff, sugar beets, corncobs, waste paper, sawdust, coffee grounds, livestock manure, slaughterhouse wastes, and other materials.

To produce exotic mushrooms, farmers "use synthetic logs, made of sawdust and other plant materials".

Shiitake is a type of mushroom. Barney (n.d.) says (p. 4):

In 1988, shiitake production in the United States was equally divided between natural logs and synthetic logs made from sawdust, straw, corncobs, and various amendments. Eight years later, synthetic log production doubled and now makes up more than 80 percent of the total.

That said, mushrooms may occasionally use mechanically harvested plants. Beyer (n.d.):

In the days of the horse and buggy, the mushroom industry provided a valuable way to dispose of a waste commodity. Today the mushroom industry supplies the same service for race tracks and boarding stables, who cannot simply throw the material away or pile it on unused land. Unfortunately, the mushroom business grew faster than the horse racing business, so their waste is now inadequate for our industries' needs and horse manure has become a costly ingredient. In addition, other materials that are more consistent incoming to the farm are preferred to the inconsistencies associated with horse manure coming from different sources. Mushroom farms use tons of second grade hay grown on thousands of acres. Which incidentally provides additional income for farmers whose land might otherwise be idle.

This page gives a relatively comprehensive list of mushroom growing substrates.

Insects don't always displace other meats

While current human-edible-insect farming is often less efficient than eating plants directly, it's more efficient than some forms of meat production. (This statement doesn't express a normative claim. Indeed, I think cattle grazing probably reduces total invertebrate suffering precisely because of the large amounts of vegetation consumed.)

However, in some cases where insect protein is promoted, it doesn't necessarily displace other forms of meat. Hence, even those who promote entomophagy to omnivores on "it's more efficient than beef" grounds may still be increasing total crop cultivation in some cases. For example:

- This page says: "Jarrod Goldin, acting CEO and co-founder of Next Millennium Farms, a Canadian cricket farm, [...] sees bug protein powder playing a role in fortifying other foods, like pasta and bread". But a lot of store-sold bread doesn't contain much animal protein. For example, a random loaf of bread that my non-vegan housemate put in my fridge has these ingredients: "Wheat Flour, Malted Barley Flour, Water, Whole Wheat Flour, Flax Seeds, Salt, Yeast." Adding insects to such bread wouldn't directly displace other animal products.

- This article quotes one person as saying: "If Pepsico starts using cricket flour as 3 per cent of Cheetos, then you’ve got a major impact." But except for some dairy products, Cheetos don't contain animal protein, and I assume the cheese couldn't be compeltely replaced.

- This article mentions "brownies fortified with a mash of the sautéed mealworms".

Maybe one could argue that people adjust their eating to achieve a target amount of protein, so eating more protein-fortified carb products would reduce their inclination to eat meat at other meals. Probably this effect would operate somewhat, but I suspect that most people's diets allow for significant variation in the percent of total calories that are protein. For example, compare high-carb vs. high-protein diets, both of which are recommended by different camps of the nutrition community.

Sometimes bugs even displace other high-protein plant ingredients. This article describes substituting walnuts with crickets in a cookie recipe. But on a per-gram basis, walnuts actually contain more protein, as well as more calories, than crickets do. Following is a list of nutrition facts per 100 grams. (I also added mushrooms—another protein-rich non-animal food—for comparison.)

| Nutrient | Crickets (source) | Walnuts (source) | Mushroom (source) |

| calories | 121 | 654 | 22 |

| protein (g) | 12.9 | 15 | 3 |

| fat (g) | 5.5 | 65 | 0 |

| carbs (g) | 5.1 | 14 | 3 |

| calcium (mg) | 75.8 | 98.0 | 3 |

| phosphorous (mg) | 185.3 | 346 | 86 |

| iron (mg) | 9.5 | 2.9 | 0.5 |

| thiamin (mg) | 0.36 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| riboflavin (mg) | 1.09 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| niacin (mg) | 3.10 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

While crickets generally have a higher nutrient density per calorie than walnuts, Fischer should presumably favor the food type (walnuts) that has more total calories and protein because then fewer grams of it need to be consumed. (Of course, one also has to consider the inputs required to produce each gram of different food types.) Meanwhile, mushrooms actually contain more protein per calorie, as well as more nutrients of many other types per calorie, than crickets do.

This page seems to imply that insect protein isn't necessarily better than soy protein? "Insect protein contains a useful level of essential amino acids, comparable with protein from soybeans, though less than in casein (found in foods such as cheese).[80]"

The entomophagy hype seems to give people a halo around eating insects, as though insects are King Midas, and any food they touch is environmentally sustainable. Maybe this marketing has been successful in part because eating insects sounds unpleasant to most people, and it's common to equate what's moral with what's unpleasant. Somehow eating more chicken, which seems to me to be pretty comparable in terms of nutritional and environmental impacts as eating grain-fed insects, doesn't carry the same (mistaken) moral glow. For other people, eating insects is a way to signal coolness and commitment, similar to donating to charity or ritually fasting.

Footnotes

- For a time, I ate dandelion leaves and flowers from my yard, rather than vegetables from the store, to save money. One reason I stopped doing so was that the dandelions often contained small bugs, which I felt really bad about injuring. However, eating wild plants along with a few bugs they might contain is surely less harmful than eating just bugs. (back)

- Note that growth in "protein output per standing livestock biomass" seems to me to mainly suggest faster growth and shorter lifespans of farm animals. This probably correlates with improved feed-conversion efficiency, since the animals aren't sticking around and wasting energy via maintenance metabolism as long, but "protein output per standing livestock biomass" is not equivalent to feed-conversion efficiency. For example, even if maintenance metabolism is ~halved by ~doubling growth speed, the animal still needs to consume feed to incorporate into its body mass. Both maintenance metabolism and body-mass anabolism are relevant to feed-conversion efficiency. (back)