Summary

This piece sketches my (perhaps inadequate) understanding of type-F monism in the philosophy of mind. I argue that the view is ultimately either a form of type-A physicalism or a form of property dualism (broadly construed). The reasons to reject property dualism also apply to property-dualist interpretations of type-F monism. In addition, type-F monism relies on categorical properties, whose existence I'm skeptical of.

Note: This piece is a work in progress. I'm not an expert on type-F monism or the debate over dispositional monism.

Contents

Introduction

Note: This piece uses the terminology of Chalmers (2003). See that article for definitions of type-A through type-F views on consciousness.

In my opinion, if you're not a type-A physicalist or an idealist regarding consciousness, then you're ultimately a property dualist, whether you admit it or not. I'll ignore idealism in this piece and focus on the contrast between type-A physicalism and property dualism. Type-A physicalists maintain that there is only physics, and phenomenal experience is an attribution we make, not a "real thing" in an ontological sense. Property dualism is the alternative view: that phenomenal experience is a "real thing" in some form. In my opinion, this is the fundamental distinction in philosophy of mind, with specific views on consciousness just being variants of these two stances. In particular, I believe that type-F monism ultimately reduces to either type-A physicalism (in its more sensible interpretations) or to property dualism (in its less sensible interpretations).

Type-A construals of type-F views

Neutral monism is one type-F view. While the views of neutral monists are generally not equivalent to type-A physicalism, at least some quotations from neutral monists can be (mis?)interpreted as expressing the same idea as type-A physicalism. One example is the following quote from Bertrand Russell, summarizing William James:

James's view is that the raw material out of which the world is built up is not of two sorts, one matter and the other mind, but that it is arranged in different patterns by its inter-relations, and that some arrangements may be called mental, while others may be called physical.

This idea of merely "calling" some things mental and others not based on their relations or functions is a type-A view. And in my opinion, it doesn't matter if we call the stuff of the world "physical" or "neutral"—it amounts to the same thing—so we may as well regard such a view as type-A physicalism. Of course, I haven't read James or Russell myself and am probably quoting them out of context.

Property-dualist construals of type-F views

Type-F views as Chalmers (2003) defines them seem to me to be property dualism in disguise. Why? Because like property dualism, type-F views maintain that there's a difference between physics and phenomenal experience, where phenomenal experience has properties/aspects/natures beyond the structural/functional dynamics of physics. This means that there are phenomenal properties that are not just the structural/functional properties of physics, which meets a broad definition of property dualism. (For similar reasons, I maintain that type-B and type-Da views are ultimately property dualism as well, broadly understood.) Indeed, Chalmers (2003) says of type-F monism:

it can be seen as a sort of dualism. The view acknowledges phenomenal or protophenomenal properties as ontologically fundamental, and it retains an underlying duality between structural-dispositional properties (those directly characterized in physical theory) and intrinsic protophenomenal properties (those responsible for consciousness). One might suggest that while the view arguably fits the letter of materialism, it shares the spirit of antimaterialism.

Arvan (2013) also uses the label of "dualism" to describe a type-F view.

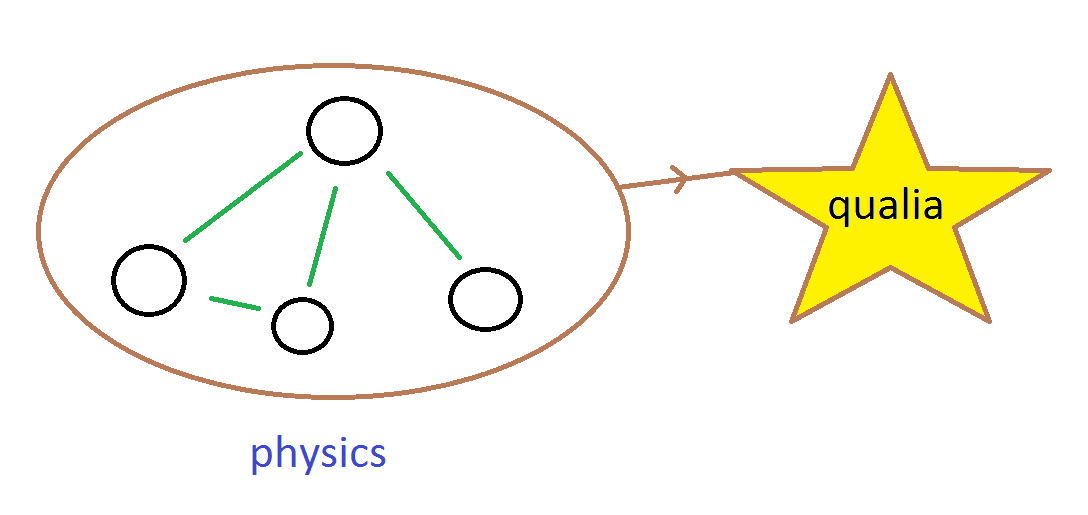

Ordinary epiphenomenalist property dualism might be pictured as follows: We have a physical world of objects with relations to one another, and then an extra property of conscious dangles (or "supervenes") on that physical system.

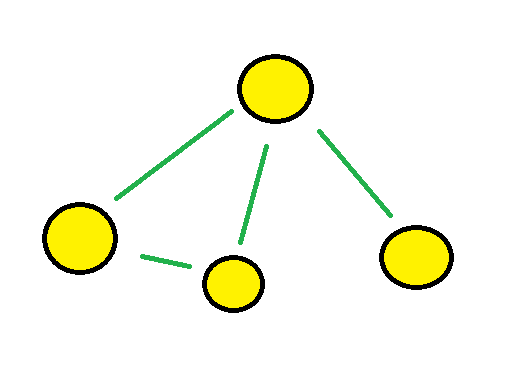

The way I picture type-F monism is that it wants to preserve the yellow star (qualia) while trying to sneak it in somewhere else. Where else can we put the yellow star? Well, we could stick it inside the entities that fundamental physics describes:

This way we can keep our qualia (the yellow stuff) without having it dangling off to the side. We can instead claim that it fits more naturally into our ontology because it's the essence physics is made of.

Shortly after writing this piece, I discovered that Goff (2017) proposes the same analogy (coloring in a picture) to describe type-F panpsychism: "All we get from physics is this big black-and-white abstract structure, which we must somehow colour in with intrinsic nature. We know how to colour in one bit of it: the brains of organisms are coloured in with experience. How to colour in the rest? The most elegant, simple, sensible option is to colour in the rest of the world with the same pen."

What's wrong with property-dualist type-F views?

Some of the below points are also discussed here.

Doesn't explain our belief in consciousness

A big problem with ordinary property dualism is that it fails to explain why our physical brains believe themselves to be conscious. If consciousness is epiphenomenal, there must be a different reason within physics that explains why we believe we have phenomenal consciousness (Yudkowsky 2008, Tomasik 2014).

With type-F monism, consciousness is not technically epiphenomenal, since physics is consciousness, but consciousness seems to still be effectively epiphenomenal in the sense that it, by itself, doesn't explain why our neurons form connections and fire in patterns that correspond to a physical belief in our own consciousness. How would the yellow stuff in the type-F picture cause my neurons to wire in the right, complex patterns to express a physical belief in my own consciousness? Unless the yellow stuff has a complex physics-guiding algorithm built into it (in which case it's part of the dispositional nature of physics, not just the categorical nature of physics), it seems to be a brute coincidence that our physical brains correctly believe themselves to be conscious.

Chalmers (1996) seems to agree (p. 181):

Even if [type-B and type-Fb] views salvage a sort of causal relevance for consciousness, they still lead to explanatory irrelevance, as explanatory relevance must be supported by conceptual connections. Even on these views, one can give a reductive explanation of phenomenal judgments but not of consciousness itself, making consciousness explanatorily irrelevant to the judgments. There will be a processing explanation of the judgments that does not invoke or imply the existence of experience at any stage; the presence of any further "metaphysically necessary" connection or intrinsic phenomenal properties will be conceptually quite independent of anything that goes into the explanation of behavior.

Combination problem

Chalmers (2003) believes that the so-called combination problem for panpsychism "is easily the most serious problem for the type-F monist view." I won't recapitulate the debate on this topic (most of which I'm unfamiliar with) other than to add my voice to the sentiment that the combination of micro-experiences into macro-experiences seems about as mysterious to me as just postulating a property-dualist form of consciousness that supervenes on ordinary physics. If we can get a macro-consciousness property from micro-consciousnesses, why not just get a macro-consciousness property from ordinary physics?

Who said anything about categorical properties?

Type-F monism tries to squeeze consciousness into the categorical properties of physics that are said to exist over and above dispositional properties, i.e., the essence of physics that exists beyond its structural/functional behavior. This is said to be one of the selling points of the type-F view, since it solves two mysteries for the price of one: (1) the existence of qualia and (2) the fundamental nature of physical stuff.

The problem is, I don't see a reason to believe in categorical properties, using the same logic by which I don't see a reason to believe in a property-dualist view of consciousness: If categorical properties did exist, how would we ever discover them? Because they're by definition not functional, there could be no causal interactions that would result in our physical brains believing they exist.

Maybe one could argue for the existence of barebones entities on a priori grounds. For example, if you want to use math to describe physical structure, you might postulate sets. The mathematical definition of a binary relation is a set of ordered pairs. And an ordered pair like (1, 2) can be defined as {{1}, {1, 2}}. And natural numbers can themselves be defined using sets. So we can express relations using sets, which can be seen as barebones "entities" in an ontology, but they're not the kinds of entities that have any content like phenomenality to them. They're more like placeholders, or arbitrary variable names in a programming language, that merely help to represent the structure. Postulating ontological primitives that have non-trivial essential properties seems to me to violate Occams's razor. All our beliefs are structural/functional, because it's only the structure/function of physics that can produce changes in our neural patterns. Nothing is gained by postulating extra properties—whether phenomenal properties or more general categorical properties.

I haven't read much about dispositional monism, so I won't commit to it just yet. My view is something like this: We use empirical observations to derive physical theories. Then the "properties" of things are exactly what's described by those theories. For example, the properties of a quantum system are just whatever the system does when you apply the Schrödinger equation (or whatever the true laws of physics are) to it. The dispositions of an entity can be "read off" of the equations of physics by seeing how the object will behave in such-and-such conditions. We can make statements about counterfactuals by imagining a world with such-and-such initial conditions and then running physical laws forward on that world.

C. B. Martin and Pythagoreanism

Esser (2013), p. 14 discusses C. B. Martin's view on categorical properties:

Purely categorical properties are intrinsically “incapable of affecting or being affected by anything else” (Martin, 2008, p. 66). They are undetectable and give us no reason to believe they exist. Postulating that they serve as grounds or bases for dispositions (or supposing that dispositions supervene on categorical properties) requires introducing a new and mysterious sort of relation into one’s ontology.

I share these critiques. But Esser (2013) continues (pp. 14-15):

pure dispositionalism becomes in the context of physics an exercise in describing causal relations solely in language of mathematics. Martin warns: “This way lies Pythagoreanism” – in other words, the temptation to think reality can somehow be purely formal or quantitative (Martin, 2008, p. 74).

But what exactly is wrong with this Pythagorean view? I haven't read Martin's 2008 book, but I did read an older article, Martin (1997), on which the relevant chapter from his book is based. In my opinion, Martin (1997) didn't really argue against Pythagoreanism so much as express the intuition that it leaves something out. For example, he calls Pythagoreanism "an unacceptably empty desert" (p. 195) and says (p. 222): "This unfettered deontologizing which results in a world of pure number seems as clear a reductio as in philosophy."

Martin (1997) adds (p. 215):

Dispositionalists believe that all that appears to be qualitatively intrinsic to things just reduces to capacities/dispositions for the formation of other capacities/dispositions for the formation of other capacities/dispositions for the formation of . . . . And, of course, the manifestations of any disposition can only be further dispositions for . . . . This image appears absurd even if one is a realist about capacities/dispositions. It is like a promissory note that may be actual enough but if it is for only another promissory note which is . . . , that is entirely too promissory.

I don't see the dispositionalist view as absurd as long as there's still some barebones way in which the structure hangs together. What we don't need are meaningful properties in addition to structure/relations. What would it even mean for there to be a substantive property that wasn't dispositional? For example, suppose you thought that the spin of an electron was a real thing over and above the ways it affected small-scale physics and chemistry. What would you even be saying? How would such an attribution of a non-placeholder "spin" property to an electron help? Of course, I also don't know what it even means to say that a physical structure/relation "exists"; in general, the field of metaphysics is beyond my ken. But at least I'm trying to minimize the number of mysteries in my ontology by only having structure/relations rather than also categorical properties.

Martin (1997) recognizes (p. 215) my argument that if a property doesn't play a functional role, it's not clear why we should believe in it: "Your knowledge of the existence of physical x or mental y has to involve the causal set of dispositions of x and y to affect your belief that x or that y. That set of dispositions is specifically operative on that occasion for that belief." But then (if I read him correctly) he rejects what I see as the approach, consistent with Occam's razor, of denying that there are further properties if they don't contribute to our belief in them: "This, however, does not establish (contra Shoemaker) that the content of what you know or believe is nothing more than the set of causal dispositions or functions that make you or would make you believe x or y."c

There seems to be a connection between people's psychological need for categorical properties in fundamental physics and people's psychological need for phenomenal properties in the philosophy of mind. Indeed, Martin (1997) uses the phrase "physical qualia" to describe categorical properties (p. 193). And he says (p. 223): "When we consider the need for physical qualia (that is, qualities), even in the finest interstices of nature, largely unregarded and unknown, among them should belong the qualia (qualities) required for the sensing and feeling parts of physical nature."

My guess is that the human brain naturally thinks in dualist/essentialist terms (Tomasik 2013), which leads to a doubling of one's ontology relative to what actually exists. An essentialist ontology contains (1) the structural/functional aspect of a thing that does all the work and (2) the "essence" of the thing, which does nothing other than making us feel better about the way the ontology looks.

Footnotes

- Consider the mental substance postulated by substance dualism. This substance interacts with the physical world, yet it also has a mental nature that physics lacks. So this substance has both functional properties (influencing physics) and qualitative properties (i.e., qualia). But this is just property dualism for the mental substance. Just as in the case of ordinary property dualism, it's unexplained how the qualitative aspects of mind can causally influence the functional aspects of mind. (back)

- Actually, in this passage, Chalmers (1996) refers to "type-C' positions". I think Chalmers (1996) uses the label "type C'" to refer to the same view as what Chalmers (2003) calls "type F". My guess is that Chalmers just changed the label for this view over time? Or is there any substantive difference? I don't have the full text of Chalmers (1996) and have not checked this point. (back)

- I should clarify that my view is not that I should only believe things exist if they causally affect my brain state. I believe that regions of spacetime exist outside my past and future light cones, because the existence of such regions is predicted by a simple set of theories/equations that correctly predict my own experiences. It's actually simpler (in a minimum-description-length kind of sense) to postulate that a massive multiverse exists of which I observe tiny pieces than to postulate that only the things I observe exist, because the equations for physics as a whole can be relatively simple. In contrast, rules for specifying what I observe at any given moment, without a broader context of the rest of the universe, are fairly complicated, because such rules presumably need to hard-code the data I observe at each time slice, which requires far more bits than are required to write the laws of physics. Or at least, one would need to compute the laws of physics anyway to know what to show me at any given moment and then restrict reality down to just what I myself observe. (Incidentally, this is also why I reject solipsistic idealism—the idea that all that exists is my own conscious state at any given time.) (back)