Summary

Hatred-based violence is a significant social problem today, and it may be among the most worrying dangers for a future civilization. I think there's value of information to exploring approaches for promoting tolerance and reducing aggressive impulses, both at the level of personal actions and at the level of political/social/religious ideologies. With this high-level context, I go on to discuss some ways of thinking about anger that I find useful for myself, although I don't claim these are necessarily solutions to the bigger-picture social issue of interpersonal hostility. I find that imagining yourself as someone else is one of the most powerful ways to feel tolerance, with the side effects of making yourself more rational and often more persuasive.

Contents

Epigraph

"one generation full of deeply loving parents would change the brain of the next generation, and with that, the world." --Dr. Charles Raison (though see also challenges to this claim)

Social importance of reducing hostility

In our evolutionary past, there were times when anger aided survival, especially in cases of revenge. In the absence of a police force and criminal-justice system, our ancestors had to rely on uncontrollable emotions of rage to serve as credible threats of punishment even after the damage had been done and the harm could not be repaired by further violence.

But in modern times, it seems there are few occasions where anger still serves a useful purpose, with some exceptions. The justice system is built for inhibiting crime, and vigilantism is actually dangerous because it can provoke a spiral of violence and because it doesn't have constraints for due process and high quality of evidence. Anger can work in personal relationships, but empirically there seems to be a strong (and presumably somewhat causal) correlation between households where disagreements are resolved in a civil way and emotional health of the parents and children. The same goes for the workplace: As far as I'm aware, positive relationships tend to lead to higher productivity (and less attrition), at least in the long run. And even in the case of crime, I've heard it claimed that prevention and rehabilitation are usually more cost-effective than harsher sentences, which are sometimes imposed to satisfy the caveman emotions of voters rather than because they serve an irreplaceable preventive function.

I'm open to hearing about instances where anger remains an important tool in modern society, but for the most part, it seems to me obsolete and, even worse, actively destructive. Not only does hatred provoke many instances of violence today (between people, groups, and nations), but it also looms among the potentially most harmful influences on humanity's future. If hateful values influenced a future artificial general intelligence, or if agents expressing such values were given free reign over a share of computational resources in the future, the result could be very bleak.

As a result, I'm open to the possibility that one of the most important projects for altruists could be to reduce inclinations toward hateful tendencies, especially those that become embodied in ideologies with appreciable power. I don't claim this is likely to be the best lever to pull on, but it might be, and it's worth exploring. Possible interventions could range from direct efforts to reduce hostility among groups of people, to promoting liberal education to broaden people's world views, to campaigns of tolerance on various issues, to biologically based "moral enhancement" technologies. Reducing aggression and violence is a field in which many, many people have invested enormous resources already, so we shouldn't expect fruits to hang low.

Personal thoughts on anger

With that broader context in place, I'll share a few observations about anger from personal experience. They don't necessarily suggest grand proposals for social change, because it's risky to generalize from one example; these are just perspectives that I find myself thinking when I'm provoked to feel annoyed or exasperated with someone. These ideas are unoriginal, and I suspect most have been written hundreds of times before.

Receiving advice

Sometimes it can be annoying if other people give you advice. You might feel insulted that they don't think your current approach is correct, or you might insist that it's none of their business to get involved. Occasionally these responses make sense, but other times they represent pride and stubbornness more than rationality. If the advice is given without malice, and unless the source is known to be untrustworthy or unhelpful, then it seems you should welcome advice as an opportunity to improve. I sometimes say, "People pay consultants for advice, so why would I object when it's given for free?" I might feel inertia against updating my views, and I might not want to admit I was wrong, but I can realize that the situation is actually positive in that it's an opportunity to learn and, as a result, to prevent suffering more effectively than I had been doing.

And if you're worried about your pride or reputation, realize that many times, especially among rationalist friends, updating in response to new evidence or arguments tends to boost your credibility. Of course, this doesn't mean you should adopt every piece of advice you're given; they all need to be taken with grains of salt, maybe even tablespoons. But peer disagreement on factual questions should be taken seriously as a general principle.a

Moral disagreements

Sometimes I find myself feeling frustrated with other people when they hold moral views that seem to me obviously misguided and even atrocious. "That's terrible!" I think to myself. "How can someone have such a backwards or barbaric opinion?" Examples abound, whether the issue is religious fundamentalism or social conservatism or willingness to increase suffering in order to create additional happiness.

There is a famous, alas almost platitudinous, quotation from To Kill a Mockingbird in which Atticus says "You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view . . . until you climb into his skin and walk around in it." I find this really helps in the case of moral disagreement. As much as I may not see eye to eye with someone, I can, for a second, imagine myself as that person—complete with his/her memories, neural wiring, and emotions. That person grew up with certain genes, was socialized in a certain environment, and has developed certain reactions. If I were that person, I can see how I would take exactly the same actions and hold exactly the same sentiments. This gives me a sense of humility and compassion, because I can realize that, "Oh yeah, this person is just executing his/her motivational drives the way I am. It's sad that we disagree, but we're both fundamentally in the same spot—doing what we're wired to do."

The same is true even for cheaters, criminals, and psychopaths. Obviously I dislike their actions and want to prevent similar things from happening in the future, but I can see how, if you have certain drives and lack certain other inhibitions, you could end up in those kinds of places. This dovetails observations about the lack of (libertarian) free will (which is a confused concept) and underscores the sentiment that no one deserves to suffer. Sometimes imposing punishment can be a necessary sacrifice to deter future crimes, but fundamentally, there's not an "essence of evil" in a person that makes it good to cause pain. Steven Pinker's The Better Angels of Our Nature suggests that the printing press helped to bring about Enlightenment reforms of religious tolerance and humane punishment in part because literature and intellectual discourse allowed people to learn what it was like to be someone other than themselves.

The stance of climbing into someone else's skin (or, rather, head) promotes a feeling of tolerance and camaraderie: We're both organisms executing our impulses, so let's work together to figure out how to compromise rather than demonizing each other. Not only is this setting a good example for the kind of tolerant society we'd like to see at large, but it's also simply more effective in most cases. One of the quickest ways to shut someone off to your position is often to advance it aggressively. Dale Carnegie observes that it's usually most persuasive to start where the other person is and explore what drives him/her to feel the way s/he does. And who knows—maybe you'll learn a thing or two yourself in the process of mutual exploration.

I also find that conversation and getting to know another person, even if only in my imagination, can reduce enmity and fear. This helps not just for other people but even for monsters, devils, and other scary characters that one might encounter in nightmares. I imagine striking up a conversation with these creatures, getting to know what are their hopes, fears, and dreams for the future. Then think about how we can work together toward those goals. For instance, does the monster really want to eat me, or does it want to satisfy its hunger in general? Maybe I could help it find a job so that it can buy artificial meats instead. And so on.

Calming down

People say it's a myth that "venting" your anger helps to release it; instead, psychologists tell us, acting out tends to make you more angry. In my personal experience, if I find myself bitter, especially without a clear reason, I think about the following quote, which has been attributed to Buddha, though it's unconfirmed: "Holding on to anger is like grasping a hot coal with the intent of throwing it at someone else; you are the one getting burned." Usually anger is at best useless and at worst counterproductive, so why make myself miserable by maintaining it? Just let it go.

Related is the Dalai Lama's suggestion that "Compassion and tolerance are not a sign of weakness, but a sign of strength." It's not an affront to your pride to not respond to something that makes you angry; rather, it shows that you're in control of your emotions if you don't lash out. Adults are better than children at dealing maturely with disagreements, due to socialization and development of the prefrontal cortex.

Annoyance

Sometimes you feel irritated with how someone is acting or what s/he is saying. There are times to step in and intervene, but often the matter isn't serious. In the latter cases, the situation is analogous to anger: The annoyance is only hurting one person—yourself.

I sometimes replace annoyance with interest. "Isn't it fascinating to learn about primate psychology by seeing how others behave?" I might think. "This is an opportunity to update my world model for how human brains work."b And of course, as before, putting yourself in the other person's skin is a universal solvent for intolerant feelings.

Jealousy

When I feel jealous of what someone else possesses (whether due to genes or upbringing) or what someone else has accomplished, it helps to feel happy for that person. After all, I would be glad to be in that person's position, so it must be a great feeling for him/her. In addition, when other people do good work, this is a wonderful thing—it means they're improving the world in significant ways, and I can feel good to be collaborating on that ultimate goal. In many cases, the best way to have the biggest impact is to empower others to do more than you could ever have done by yourself.

It gets trickier in cases where the work someone else is accomplishing is not something you support, but you can still feel happy for that person as a person, and you can also respect that person's commitment to what s/he cares about. If nothing else, it's inspiring.

Life doesn't need to be a competition, because our value doesn't come from being better than others. It comes from working together to contribute to a cause larger than ourselves. This doesn't mean we don't care about our productivity or effectiveness, but we care about those things because they matter to the organisms we're trying to help, not because we need to win the game. We're each at different places, with different strengths and talents, so what matters is how well we're doing relative to what our own endowments allow us to accomplish, without burning out or feeling bad about ourselves.

I suppose there are people who are really motivated by competition and not by altruism. In this case, maybe it's okay to let them stay in their competitive world if it does more to help others. But if, like me, you find the world of competition degrading, the alternate mindset I'm proposing is available. In any event, since competition isn't always focused on reducing suffering, it can push in orthogonal directions. Sometimes it's just by accident that people compete to be more altruistic than each other.

Blame

To some degree, blame is a form of social punishment for wrong actions, and to this extent, it may be a necessary evil, especially when a rule was clearly and intentionally violated. However, there are other times when blame can be thrown around needlessly, as a form of scapegoating or revenge. Sometimes people blame themselves without good reason.

The important question is, What can we do better next time? In many cases, there's not a single individual responsible, but rather everyone could participate in improving future outcomes. Often events snowball into a big soup, without a clear originator. This is brilliantly portrayed in the song "Your Fault" from Into the Woods.

Boredom

It's a tragedy that some of the cruel actions in the world are done out of nothing more than boredom and a desire for entertainment. This is also true for actions that are (probably) currently harmless but don't bode well for the future, like Norn torture. In these cases, the best approach may be to show people that other activities can be at least as stimulating. The world has so many interesting things to explore and important projects to work on, and these can provide a deep meaning to one's life. Helping more people find this—whether through education, constructive gaming, genetic/chemical enhancements, or other means—seems useful, although probably its priority is a step lower than that of preventing active hatred-based violence.

Qualifications

Sebastian Leugger suggested that a certain type of anger may indeed have an important function: "Anger is a social emotion and it is capable of influencing others to take the issue you are angry about just as seriously as you are." This poses an interesting question: Should we use anger, or as Ralph Nader called it, "the gift of outrage," to arouse people toward fixing world problems? Or does doing so run the risk not just of alienating those you're trying to influence but also of polarizing the debate such that mutual understanding and willingness to compromise are lost? I personally err on the side of calm and friendly persuasion, and I think that even if a more confrontational approach works in the short term, it may do so at the expense of important longer-term values of amicable discourse. But it's not an open-and-shut case, and empirical research bears on the question. There's also a spectrum as far as when outrage is friendly vs. when it becomes aggressive.

While I personally don't find anger to ever be a useful emotion, it would be presumptuous to suggest that this must be true for others as well. Maybe others are more motivated to do good by righteous anger than by other emotions, and maybe expressing harmless anger in private is not something that we should all try to eliminate, especially if doing so requires too much effort. People are diverse, and there may be a place for certain kinds of anger even in an ideal society. It would be fascinating to explore these intricacies in more depth, but this doesn't take away from the seriousness of more severe and violent forms of hatred, which I think most of us agree should be replaced with positive social energy.

Replacing anger with positive emotions

The opposite of anger is not apathy, except in a few cases like when you're annoyed at something completely trivial. It's cliche but true that there are many constructive ways to resolve the conditions that led to anger, such as open dialogue with the other side so as to reach compromise or at least mutual understanding.

It can be natural to feel outraged at intolerance, hatred, and cruelty. But we should make sure to channel this outrage into constructive projects rather than just shouting at the other side, which tends to harden opposition. The parable of "The North Wind and the Sun" is instructive. We can set an example to others of a social community in which caring for others and embracing diversity are driving forces.

Social dynamics can matter a lot. In a dog-eat-dog culture, talking badly about others may be a way to have fun, make connections, and feel better about yourself. In physically violent situations, appearing intimidating may help prevent you from being attacked.

Yet these dynamics are malleable, as we can see from the range of cooperation vs. conflict among humans and even in other animals. The story in "Emergence of a Peaceful Culture in Wild Baboons" is a powerful illustration of how historical contingencies in culture may affect levels of stress, aggression, and violence in non-human societies.

The causes of hostility are multifold—some genetic, some developmental, some cultural. There are probably evolutionary drives toward aggression, and these should be considered when evaluating possible interventions. That said, it seems many proximate instances of violence are due to "nurture" factors. Here too the explanations are complex, including poverty and ideology. One broad category of "nurture" causes is what James Doty describes as follows:

The vast majority of people who are in jail are not because they're bad people. Most of the people in jail are there because they have not been given love and kindness in their lives. It's because the simple act of caring for another has not been available to them [...].

In the "Spoon Mountain" episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, Bob Trow sang the following (~19:40-20:30):

All I ever wanted was a spoon, a spoon.

A spoon was all I ever wanted.

But all they ever gave me was a knife and fork.

They even called me Wicked Knife and Fork.

And even though I hated all those knives and forks

(I was scared to death of all those knives and forks)

they never gave me a spoon, a spoon.

They never gave me a spoon.

And so I grew, to become a shrew.

And tried to undo everything that was true.

But all I ever wanted was a spoon, a spoon.

A spoon was all I ever wanted.

The transformative possibilities of love and friendship are inspiring to me.

Of course, this is not the whole story. There are many empirical details of psychology, sociology, and public policy to be worked out. We also need to evaluate which levers (cultural, educational, biological) can give the greatest returns.

Footnotes

- Disagreements are data that your world model needs to explain. Being angry with an epistemic peer for disagreeing would be like burning up your laboratory measurements because they didn't jive with your current hypothesis. Of course, your peers may genuinely be biased or unreasonable, and if so, it's easier to explain away the disagreement without updating your own view. But be wary of doing that too often, especially with people who have studied the matter in depth. (back)

-

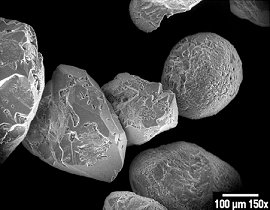

Sometimes people have the attitude that only certain experiences are insightful, while the rest (say, doing your taxes) are worthless. While I agree that repetitive experiences have diminishing returns, I don't believe that some activities are astronomically more insight-producing than others. Everything in the world gives you data with which to update your world model, and everything in the world obeys the same physical and mathematical principles as everything else.

From the study of that single pebble you could see the laws of physics and all they imply. Thinking about those laws of physics, you can see that planets will form, and you can guess that the pebble came from such a planet. The internal crystals and molecular formations of the pebble formed under gravity, which tells you something about the planet's mass; the mix of elements in the pebble tells you something about the planet's formation.

This point gives deep meaning to William Blake's first stanza of Auguries of Innocence:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.Math is powerful, and the general principles of the universe show their faces everywhere.

Of course, it helps if you can stand on the shoulders of giants so that you have much more data and don't have to recompute everything yourself. You do not in fact have the unlimited computational power of an idealized superintelligence.