Summary

Internal rates of return for charity are high, but they may not be as high as they seem naively. Haste is important, but because long-term growth is logistic rather than exponential, it's less important than has been suggested by some. That said, if artificial general intelligence (AGI) comes soon and exponential growth does not level off too quickly, naive haste may still be roughly appropriate. There are other factors for and against haste that parallel donate-vs.-invest considerations.

Restating the summary in simpler language: Movements should saturate or at least show diminishing returns at some point, so that movement building sooner amounts to either just a few more years of the movement existing or only modest marginal increases in the movement's size. These impacts could still matter—they're just not as extreme as in a naive model in which, if it takes 2 years to create a hard-core altruist, then starting 2 years earlier doubles the long-term number of altruists.

Contents

Introduction

In a thought-provoking blog post on 80,000 Hours, M. Wage describes "The haste consideration" for altruists. The idea is that if you can convince someone else to become as passionate and effective at altruism as you are, then you will have done as much good as if you had spent a lifetime on altruism yourself. I believe this is equivalent to thinking in terms of internal rates of return on activism, where the annual rate of return r is such that (1+r)N = 2 for N being how many years it takes to create another person like yourself.

On further examination, I think the haste consideration is overly optimistic about the time-value of activism, as I explain below.

Exponential returns?

The Earth currently allows for year-over-year economic growth that compounds exponentially. Right now, if you have $94 today, you can turn it into, say, $100 next year by investing in capital markets. But exponential growth can't occur forever. Eventually, the galaxy would be colonized to its maximum level, resource extraction would be as efficient as is physically possible, and there wouldn't be room left to grow. Maybe people could keep pushing farther and farther into space, but even if we could do that and if the resources further out in space were equally useable as those nearby, the volume occupied would be proportional to the cube of time since expansion (or even less given that space is expanding exponentially too).

Now, maybe weird physics scenarios would allow for eternal exponential growth, but our default assumption is that growth will eventually have to end.

(Note: I'm not supporting the expansion of humanity throughout the galaxy, because I think this could spread wild-animal suffering, sentient simulations, suffering subroutines, etc. I'm just pretending to be an economist for purposes of illustration.)

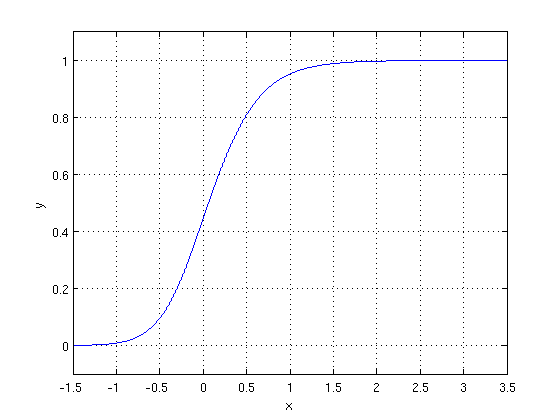

Now, suppose that unlike normal people who only worry about wealth in their lifetimes, you cared about the sum of total wealth over the whole future. At the beginning, the growth of wealth is basically exponential, but toward the end, it would be bounded. The overall growth curve might be logistic.

Take a simple example of logistic growth. The numbers represent wealth in each time period:

If you'll only live for 5 years, the growth looks basically exponential to you—with an almost 100% annual rate of return. But what if you care about the sum total of wealth over all time? Right now, the sum total is 884. If you sped things up one year, say by changing the first "1" into a "2":

then the sum total of wealth would be 933, which is a 5.5% return. It's far less than the apparent 100% return that you saw during your lifetime.

Altruism examples

The same idea has many applications. For example, it's tempting to suggest that promoting veg*ism has a high internal rate of return (say, 20%) because when we create new veg*ans, they go on to convert their friends and family. This is true, but even if we see veg*ism growing 20% (say) year over year, this doesn't mean necessarily that veg outreach now is 20% more important than veg outreach next year. For example, if everyone would eventually become veg anyway, we would be only be shifting the logistic curve left, like in the above example, and the total returns in terms of reduced suffering would be far more modest.

One can make similar comparisons for most altruistic projects: Promoting economic development, building a new movement, etc.

It's important to note that I'm not saying activism is useless. For example, if we don't raise concern for the suffering of wild animals, maybe society will never come to adopt that position. Maybe it will instead slide toward deep ecology and spreading life far and wide throughout the universe. So even if the growth of the movement to prevent the spread of wild-animal suffering is logistic, working on the issue can tip the balance between which future we end up with for billions of years to come. Thus, the work definitely needs to be done. It's just that doing it next year may not be substantially worse than doing it today.

Movements rise and fall

I think even a logistic model of social-movement growth is too generous. Most social movements of the past are extinct today. Some social movements are less active because they've largely won (e.g., abolition of slavery in developed countries), and many others are less active because they've lost influence (e.g., opposition to interracial marriage in the United States). Even recent movements like Occupy Wall Street tend to experience only a brief time in the limelight before other trends capture people's interest. So it's naive to think that spreading "effective altruism" now leads to a permanent increase in movement size for the indefinite future. It might seem that way as the movement is growing, but sooner or later, most movements eventually shrink, as people's attention is captured by other things.

When I think about the online communities of which I've been a part in the past, a significant number of them are now extinct or at least attenuated. This is a microcosm of how broader social movements wax and wane. Of course, these communities had important and lasting impacts, but those impacts would not have been many times smaller had they come a few years later.

So haste doesn't necessarily create a significant increase in the impact of a social movement. It may just move forward in time the social movement's peak impact before its later decline. Of course, in many cases there are lingering effects of past social movements on the future even if the core movement has dwindled, so it's probably generally better for the movement to happen sooner, but the magnitude of the effect plausibly isn't huge in many cases.

Were activists in the 1970s extraordinarily important?

As another gut check of the haste consideration, we could ask whether altruists in, say, the 1970s should have used haste reasoning. Suppose a given activist movement from that decade was growing at a rate of 50% per year. Should these activists have reasoned that a person-year of work applied toward the movement in 1975 was 1.510 = 58 times more important than a person-year applied toward it in 1985? And 1.530 = 191,751 times more important than a person-year applied toward the movement in 2005? Is it really plausible that altruistic work done by one person in your parents' generation was equally important as the altruistic work of almost 200,000 people in your generation?

Maybe if you're lucky enough to be someone like Peter Singer, who helped to found the modern Western animal-rights movement, then one person's impact in the 1970s could balloon into work by hundreds of thousands of people on the cause within a few decades. However, situations like this are extremely rare, and most of the time you should assume that your impact will be much more modest, contributing one small piece of a much larger movement. Plus, while I don't know much history of the modern animal-rights movement, I presume that the movement would still have emerged in some form without Singer, perhaps slightly smaller or delayed by a few years.

Reasons for haste

All of that said, there remain reasons why altruism sooner is more important than altruism later.

1. AGI

The human futures where the most suffering is on the line are those futures where humans develop AGI that shapes the course of our future light cone. It's possible that when the AGI is created, certain values will be locked in and maintained by goal-preservation mechanisms. If so, then shaping humanity's values would matter a lot before that locking in happens but hardly at all afterward.

In this case, there is indeed a sort of "lifetime" put on our activism: What we do only matters until AGI comes along. (If AGI doesn't ever come along, what we do doesn't matter nearly as much anyway, so we can ignore those scenarios.) If our influence on AGI is a monotonically increasing function of the amount of support we have at the point of AGI's arrival, then a year of extra haste could matter a lot, depending on when the logistic plateau happens. If it happens relatively soon (within a few decades), then likely haste won't have a huge effect on AGI. If the growth curve continues to be steep at AGI-time, then starting a year or two earlier would have been quite a bit better.

2. Burnout risks

Each of us has a risk of jumping off the altruism boat. It may seem hard to imagine now, but as people age, they become less idealistic and change their habits and preferences. For example:

A study led by Harvard University psychologists reveals that this is a systematic and fundamental perceptual mistake. People of all ages can clearly see how they changed and matured over the past decade, but both younger and older people underestimate the amount they will change over the next 10 years. They seem to suffer from the delusion that the person they've become is the real version. The researchers call it the "end of history illusion."

This means you should discount your future years according to the probability that you will have become disillusioned and apathetic by that time. This consideration creates a "discount rate" of its own.

3. Financial returns

Exponential returns in capital markets will probably continue for several decades, so to some extent, they can be a lower bound on the rate of return that you should use for future years when it comes to financial matters. For example, if you're deciding whether to do fundraising this year or next year, doing it this year is at least ~7% better in expectation—or whatever percentage you think is appropriate for real rates of return on the stock market—because the money will grow by next year. There may be diminishing returns to wealth, which need to be factored in.

4. Other things

As the world population grows, your proportional share of influence over humanity may decline a little. As wealth and power grow around you, you have to run just to stay in place. There may be other effects like these that militate in favor of acting sooner.

Reasons for patience

This essay has by now become a lot like the "Donate vs. Invest" thread on Felicifia. There, we cited the single most important reason why young grasshoppers should exercise patience: Returns on wisdom. There's a lot to learn, and even after studying these matters for many years, my estimates of cost-effectiveness of various options change by factors of 1.5, 3, 10, 100, etc. They may even change sign.

These factors may easily exceed internal rates of return on direct activism. But realize that direct activism is one of the best ways to learn about the world in the first place (as well as to reduce your risk of burnout), so I don't think that patience and haste are completely incompatible: I think doing things now but reserving substantial time for longer-term reflection on the global landscape of cost-effectiveness maybe the best approach. You can't get a complete picture of how to do effective activism from an armchair—you have to actually spend some time trying it. But you also should avoid getting so caught up in the day-to-day details that you neglect broader contemplation.

Relevant comments from others

Here are some snippets from the comments on the original "haste consideration" thread that coincide with my remarks.

Zander Redwood:

all this seems to assume exponential growth of the EA sentiment given enough persuaders, but that seems ultra-optimistic. More likely we'll quickly hit diminishing returns. The current members of 80K and GWWC are approximately the most enthusiastic and (given their Oxbridge/Ivy League locations) have some of the brightest futures of anyone in England and the US. Granted there's still quite a lot of room to reach people, but basically the members we attract over the next couple of years will be the lowest hanging fruit.

Toby Ord:

1) The consideration that at the start of a movement, movement building could easily be the most important thing to work on is pretty solid and uncontroversial. People often say: but your doing X alone won't change much, you need to try to get thousands of people to start doing it. Or consider whether the founders of Google should have spent all their time coding or instead spent some of it hiring people to code, then also hiring people to do human resources (i.e. hiring to hire).

Sure it is slightly recursive, but there is nothing paradoxical about the basic structure, and on examination it is clearly not a pyramid scheme. Pyramid schemes are attempts to get benefits from people in the levels below you, who get benefits from those in the levels below them, which fails for many of the people because the population is finite. This is not what is happening here, as there is actually no private benefit passing at all, just a group of people working together.

2) The argument is about growing an organisation or movement in a lasting way. I agree with Ruairi that If one merely tried to get people involved to get people involved etc, you wouldn't get much overall sustained growth (even if there was a promised future point at which they start doing first order work). It would be much more effective at convincing people to join if a large part of the organisation's time was spent on first order work (maybe half?). This is true for 80,000 Hours and would have been true for other organisations such as Google or various movements.

3) I think the haste part of the argument (as opposed to the growth in general part) is sensitive to questions about how the rate of getting people to join drops off (e.g. is there an ultimate S-curve and what is the probability distribution of whether we reach that point). e.g. for simplicity, if there are only 4 people interested, then one might be able to convince them all early on, or later.

Cause-specific haste vs. broader patience

In "Why Now Matters", Nate Soares says of MIRI: "I would very likely take $10M today over $20M in five years." This implies an annual discount rate of ~15%, which is higher than the ~5% returns one can earn on the stock market. (In other words, Nate's trade ratio implies a ~10% discount rate on timing of MIRI's work independent of stock-market investing.) One of Nate's arguments is that AGI-safety research will have more funding in the future. In itself, this isn't an argument for haste, since if that future funding were guaranteed, current donations would only be incremental on future donations and so might have low marginal value. If the money donated now didn't specially affect short-term trajectories, then donating $1M now and $20M later would be comparable to donating $21M later. But two stronger points are that

- whether and how much future funding comes in may depend on current donations in this time-sensitive window, and

- funding MIRI early will allow it to have bigger influence on the field of AGI safety as a whole when AGI safety becomes better funded in the near future.

I'm not sure if I agree with Nate's exact tradeoff between present vs. future MIRI donations, but his points are sensible.

If one does accept Nate's time-money tradeoff, does this mean we should use a 15% - 5% = 10% discount rate for the haste consideration? No. (At least not automatically.) While it may be true that MIRI has a crucial funding window right now, in 5 years' time, if AGI safety becomes more saturated, other causes will still have high marginal returns to funding. Opportunities to do essential altruistic work don't all decline at a rate of 10% per year; rather, new opportunities arise as others fall away. Funding charity is like finding undervalued companies: Just because a company won't be undervalued anymore a few months from now doesn't mean you won't be able to find any other comparably good undervalued companies beyond a few months out.

In aggregate, probably an inflation-adjusted dollar in 2030 would buy less altruistic impact than an inflation-adjusted dollar in 2000, but not 1.130 = 17 times less impact, which is what would be implied by a 10% altruistic discount rate above a discount rate based on stock-market returns. If you're skeptical about this future-oriented prediction, then imagine the difference between altruism in 1970 vs. 2000. Did an inflation-adjusted dollar in 1970 have 17 times more impact? And if your response is: "But right now is a special time in human history, so dollars are particularly valuable now, whereas they weren't in 1970", you need good reasons for thinking so, given that it's common for each generation to believe that it occupies a privileged position.

Future work on this topic

In general, it's hard to compute internal rates of return from charitable activities. We don't know the parameters (length, height, slope) of the logistic curve we face, so it's difficult to estimate the value of shifting it left by some amount, especially given the uncertainty over when AGI happens. Maybe the EA community will eventually build better frameworks of thought in this regard. It's quite possible such frameworks already exist and we haven't discovered them yet—surely economists must have decision models beyond exponential discounting?

Feedback

For comments on this piece, see the original Felicifia thread.