Summary

This piece collects some observations about Nick Bostrom's simulation argument and its implications for altruism and how we see our world. The text is mostly copied from a 2013 Felicifia thread.

Contents

A few possible motivations for simulations

Here's a non-exhaustive list of some potential reasons why advanced civilizations might run simulations of Earth.

- Studying the distribution of civilizations in the universe: It's possible that a convergent subgoal of many advanced civilizations will be to learn about the distribution of life forms in the universe. This would be useful for, among other things, anticipating how likely an encounter with aliens is and what their values might be. One way to study the distribution of life in the universe could be to run large numbers of moderately accurate simulations of evolution across a wide variety of planets.

- Intrinsic value: Some civilizations may find it intrinsically valuable to simulate their ancestors or other alien civilizations, such as because they place intrinsic value on creating a variety of autonomous creatures or because they want to observe interesting stories play out. As an analogy, some humans keep pet fish or ant farms for similar reasons.

- Studying history: People often debate historical counterfactuals like "What if the South had won the US Civil War?" Simulations allow for finding out the answers to such questions to a greater degree of accuracy than we can with more computationally limited analysis.

- Games / virtual reality: Future people might enjoy diving into past worlds in order to interact with simulated people in lifelike settings. Hanson (2001): "We expect our descendants to run histori[c]al simulations for several different kinds of reasons. First, some historical simulations will be run for academic or intellectual interest, in order to learn more about what actually happened in the past, or about how history would have changed if conditions had changed. Other historical simulations, however, perhaps the vast majority, will be created for their story-telling and entertainment value. For example, someone might ask their 'holodeck' to let them play a famous movie actor at a party at the turn of the mille[n]nium."

- Exploring the space of values: While I find this scenario relatively unlikely, one could imagine that future people want to investigate the distribution of what moral values they would have adopted if they had had a range of possible initial conditions for their moral development. If some moral views are more convergent than others across the range of initial conditions, those more convergent moral views may be better candidates for "idealized" morality. (Thanks to a friend for inspiring this suggestion.)

Given the immense suffering our world contains, we can infer that our simulators either aren't very compassionate, or they believe that the ends justify the means and that some simulations that include horrific suffering are necessary. There's also a small chance that the worst forms of suffering in our world are faked, although if you are one of those currently suffering beings, you can see that this is untrue for you at that moment.

Human-type compassion is relatively rare among animals, and it's plausible that most artificial intelligences would also not feel compassion for powerless creatures. For this reason, it seems most likely to me that if we're in a simulation, the suffering in our world results from indifference.

Are most ancestor simulations fictional?

Based on Nick Bostrom's simulation argument, I think it's not unlikely that we're in a simulation. But what kind is it? Is it a full-scale replication of the history of the basement universe? Or is it something more specific and unrealistic? In the past, I have, by habit, tended to imagine the former, but now I realize that it's most likely the latter.

In particular, it would be really expensive to simulate physics. If the simulators wanted to make the world accurate relative to the observations that people make, they'd have to go down to the quantum level, because people do make quantum-level observations. But this would be prohibitively costly. Think of how much computing power we'd need to simulate a single quantum particle accurately. Simulating a quantity X of physics probably requires many times X amount of computer hardware. So unless the simulation is running in a basement universe that's much bigger or allows for much easier computation, the simulation is unlikely to have quantum-level fidelity.

But then how do we explain the consistency of our observations of quantum physics? Here's Bostrom's suggestion from his original paper:

Simulating the entire universe down to the quantum level is obviously infeasible, unless radically new physics is discovered. But in order to get a realistic simulation of human experience, much less is needed – only whatever is required to ensure that the simulated humans, interacting in normal human ways with their simulated environment, don’t notice any irregularities. The microscopic structure of the inside of the Earth can be safely omitted. Distant astronomical objects can have highly compressed representations: verisimilitude need extend to the narrow band of properties that we can observe from our planet or solar system spacecraft. On the surface of Earth, macroscopic objects in inhabited areas may need to be continuously simulated, but microscopic phenomena could likely be filled in ad hoc. [...]

Moreover, a posthuman simulator would have enough computing power to keep track of the detailed belief-states in all human brains at all times. Therefore, when it saw that a human was about to make an observation of the microscopic world, it could fill in sufficient detail in the simulation in the appropriate domain on an as-needed basis. Should any error occur, the director could easily edit the states of any brains that have become aware of an anomaly before it spoils the simulation. Alternatively, the director could skip back a few seconds and rerun the simulation in a way that avoids the problem.

Keeping track of the belief states of all minds seems like a lot of work. Maybe it wouldn't require vast computing power, but it would be a challenging software problem, because you'd need a classifier to map from brain-state data to a semantic label that "Harry believes X", etc.

In any event, the implication of all this is that if we're in a simulation, the physics that we observe is probably stylized and mostly absent. Maybe the physical laws of our simulation are approximately correct to a degree that's cheap to compute, but they're probably not correct down to every quantum particle, or maybe even to every cell. The cheapest experiences to create would be just brains with very shady input from the environment.

And, by consequence, it seems unlikely that our simulation is a near-exact replica of the way things were in the real basement universe, because it's too expensive to compute how things really were. Of course, people kept history books and took video recordings, and those could help stitch together a rough picture. But our simulated experiences would then be akin to a movie reenactment of the fall of Julius Caesar: The costumes and events and environment might be about right, but the simulation would be making up the gaps that were lost to history.

Non-causal decision theories suggests that even if we are in a simulation, our choices can still matter a lot if they correspond to choices that our same brains made in the basement universe. But if we're not an exact simulation of the basement universe, then it seems our ability to influence the basement is less than we might have thought. Still, if there are lots of simulations of minds close to what was in the basement (e.g., people narcissistically creating vast copies of their former selves with approximately realistic environments), the correspondence may still hold enough to matter, but I don't know how much. Perhaps the simulation is only being held on the right track to correspond with historical reality through artificial revisions, because the environment and choices of the simulated mind aren't close enough to what happened in the basement due to butterfly effects resulting from the insufficient level of detail?

Solipsism?

If I am in a sim where the external world is only adumbrated rather than thoroughly computed, does this imply solipsism? Maybe it increases the chance somewhat. For example, maybe my future self became wealthy and powerful and decided to simulate gazillions of copies of himself, without simulating other people and animals along for the ride. That said, I hope this isn't the case, because I would prefer my future self to use his resources for reducing suffering rather than reproducing his past life over and over. (And I'm a negative utilitarian anyway.) Of course, solipsistic simulations of me could also be run by other agents besides my future self, but in this case, it's less clear why they're singling out just one mind to focus on.

Also, the agents that I interact with (people and animals) seem pretty realistic, and in order to compute some of their reactions to what I do, you'd probably need a good amount of their minds being run as well. In general, it seems easier to just run their minds too, and let the different minds interact. The sim would then be like a MMOG, and instead of wasting resources trying to fake the external minds like in the solipsistic scenario, you'd actually have the other minds for real. Presumably this would let the simulators run more minds per unit of computation, memory, storage, etc.

Altruism still matters

So, maybe a good way to imagine our sim is as a MMOG. In this context, our actions do affect the welfare of others, just like they do if we're not in a sim. The MMOG has its own laws of physics, and what we do physically causes injury or benefit to our companions. It doesn't matter that quantum-level phenomena aren't being simulated. Altruism, arguably, makes just as much of a difference in a world where Newtonian physics engines are used as in a world where the universe is actually evolving according to the Schrodinger equation.

Our observations of the reliability of cause and effect would still be valid in a sim, and evidence-based assessments of which types of interventions will do the most good would still be prudent. Studies on animal sentience would still make sense, because if we see animals acting in complex ways, it could become more parsimonious to suppose that their minds are being simulated along with ours rather than that they're an elaborate, stylized presentation to our senses.

In a sim, apparent violations of physics, causality, etc. wouldn't be as heavily penalized by Occam's razor, because these things wouldn't actually violate physical law at all. But such a violation would still require special logic in the software, or special actions on the part of the simulation overseers. So there would still be a modest Occam penalty, and in any case, empirically, we don't see many such violations. But the probability of paranormal explanations for weird things does increase a little.

If we are in a sim, then maybe we'd expect our lives could be cut short, if the simulators decide to end things early. Like Last Thursdayism suggests, we might also have been created just recently, rather than having gone through our whole lives to this point. However, the setup of our world is pretty elaborate—especially our memories—and it's possible that the easiest way to get our memories and world-state to be the way they are is actually just to run the whole thing from scratch, rather than trying to set up the conditions correctly. Programmers will tell you that when you're trying to debug your code, it can be easiest just to rerun the program from the beginning and set a breakpoint rather than trying to change the state variables to mimic the point of the program that you're interested in. In theory, I suppose the simulators could have run the world once and stored data dumps at different points in history, so that they could then re-load the world at a desired point without recomputing the whole thing.

In any event, we have to remember that we may in fact not be in a sim. I don't know what probability to give, but say there's at least a 30% chance we're in the "real world". Contributing factors to this probability are the possibility that advanced civilizations don't acquire lots of computing power, the possibility that they don't do these kinds of sims much, the possibility that our reasoning about the simulation argument is flawed, etc.

Finally, remember non-causal decision theories: Even if we were a solipsistic simulation, we're still instantiating cognitive algorithms that are common to other minds, including minds in the basement. If we exhibit altruism, this contributes—to some degree—to their exhibiting altruism as well.

Motivations for simulating?

Of all the things post-humans could simulate, why would they choose minds like ours? Why not something happier, or at least more interesting and complicated? Judging from the suffering in our world, it seems our simulators are not particularly compassionate.

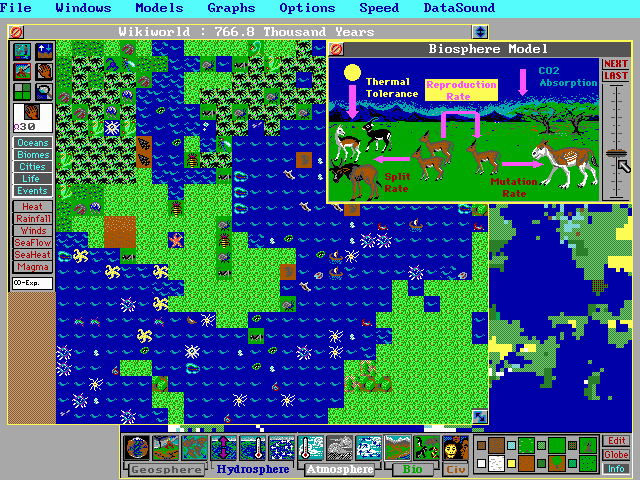

If we look around today at why people build virtual worlds, the reason is usually for entertainment, rather than for industry or science. That said, in video games, the protagonists are not autonomous minds the way you and I (presumably) are. It's less fun to play a video game where you just watch self-directed creatures do stuff, unless the purpose is to be more like a movie than a video game. But if it's just like a movie, then why not record it once and replay the same thing to everyone? You don't need large numbers of copies of the sim for that.

If we look around today at why people build virtual worlds, the reason is usually for entertainment, rather than for industry or science. That said, in video games, the protagonists are not autonomous minds the way you and I (presumably) are. It's less fun to play a video game where you just watch self-directed creatures do stuff, unless the purpose is to be more like a movie than a video game. But if it's just like a movie, then why not record it once and replay the same thing to everyone? You don't need large numbers of copies of the sim for that.

Video games do have autonomous agents, but they're most often the villains—the goombas and sandworms and Skulltulas and Bowsers. They might also be the fellow denizens of the world who aren't the protagonist. Assuming we're not enemies, maybe we're in this latter category: We're co-inhabitants of the virtual world who interact with the post-human game players.

As suggested earlier, it's also possible that we're the product of narcissistic minds who wanted to create lots of copies of their past lives.

Maybe we're being run by people who value "life as it used to be" or "historical preservation" or some other unpleasant thing.

Some virtual agents today are run for scientific purposes—to refine AI models of organisms. I suspect these are dwarfed by game AIs, but maybe this won't always be the case, especially if the AIs that survive the best highly value science rather than leisure.

Are there industrial applications of virtual-world sims? I can't think of many offhand. It's not as though we're performing a useful data-processing task or solving a computational problem—except just to discover the computational result of a world with our initial conditions.

Why is physics so complicated?

Among many puzzles of our potential simulation is why the simulators have made physics look so complicated. I'm guessing it's a lot simpler to apply Newtonian mechanics to macroscopic bodies than to have small particles exhibit quantum phenomena. Why have our simulators included quantum physics, complicated particle physics, and all sorts of tough questions that physicists are still puzzling over?

There are plenty of other hard problems about which one could ask the same questions—in biology, economics, psychology, etc. But at least there, it's plausible that the complexity arises organically from the interactions of high-fidelity sims of minds. If there aren't high-fidelity sims of physics down to the quantum level, why pretend that physics is so complicated when we examine it in the lab?